Apples

Helen Hokin celebrates England’s beloved fruit and its many varieties, making use of a rich tradition of recipes

Brace yourself for a rare British food story with a happy ending: after clashes of titanic proportions, lasting more than two decades, English apple growers and the major multiples appear to be living harmoniously ever after. A good news story for an industry that just five years ago was on its knees. By 2003, despite bumper crops and sublime eating quality, the English apple industry had plummeted into crisis as supermarkets continued to eschew home-grown varieties in favour of cheap imports. Farmers in Kent, Somerset, Sussex and Surrey were faced with little alternative but to use their orchards for something else as the registered number of English apple-growers fell from 1,500 in 1987 to a mere 500 in 2003.

Fingers were pointed; growers and consumer groups blamed the supermarkets for buying overseas and paying lip service to British produce. Supermarkets blamed the consumers’ alleged inability to see beyond the perfectly formed French Golden Delicious, insisting they’d lose millions if they stocked the knobbly apples grown at home. Finally, the trade association, English Apples and Pears, stepped in and a light-bulb moment was reached. Yes, it is in everyone’s interest to nurture and celebrate a centuries-old industry, not to mention preserve our beautiful orchards.

Three years on and our packed lunches and pies feature English apples once more. Admittedly, the choice of cultivars in supermarkets remains largely unadventurous: Braeburn, Gala and Cox, but at least they bear the Union Jack sticker. It’s a good start. ‘English apple production will double in the next five years,’ says English Apples and Pears’ chief executive, Adrian Barlow. While he recognises it will take some convincing to get supermarkets to broaden their range, he confirms that the heritage Egremont Russet has been welcomed by consumers. Culinary varieties are also, reportedly, flying out the door; growers can barely satisfy the demand of a post ready-meal Britain that is rediscovering the joys of home-made crumbles and pies.

If that wasn’t enough good news for one rescued ingredient, there is a further, happy twist to the tale. We don’t need to wait for supermarkets to gradually bring diversity to our door because farmers’ markets – the hub of the rare variety renaissance – are already there.

A range of flavours and textures are cultivated, and shades differ from lemon-yellow to deep gold, sunset pink to russet, acid-green to purple. Inside, they might be soft and mealy or firm and crisp. Tart or sweet, bumpy, elongated, striated or speckled; all exhibit characteristics of the soil and climate of the county they grew in. Rarely will you find a perfect sphere but one bite and you’re smitten, proving beauty isn’t skin deep.

If taste alone doesn’t entice then surely the names do; who could resist Foxwhelp, Cornish Gilliflower and Carlisle Codlin? Bedfordshire boasts the Lord Lambourne with orange-green flushed skin and juicy, creamy flesh. Gloucestershire gave rise to the Ashmead’s Kernel; dating back to the early 1700s, its sweet, sharp taste is bursting with aromatics. Hertfordshire is home to the Golden Reinette, dubbed ‘the farmers’ favourite’ it was brought to the county from London in the late 1850s where it thrived in the sun-warmed soil. The north produces its fair share too, like the Duke of Devonshire, first cultivated by the Duke’s gardener at Holker Hall in Lancashire; its high acidity means it’s best eaten late in the season. The further north you go the tarter they get – Stirlingshire’s early Stirling Castle is a robust cooking apple used in pies and tarts since the 1830s.

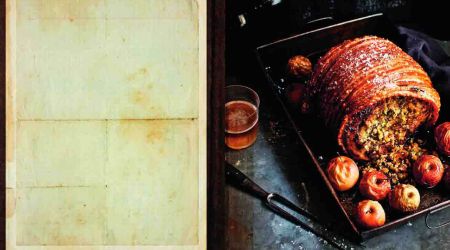

The Victorians cross-pollinated and hybridised to find the ultimate cultivar for every recipe known to them. They settled on Summer Codlins for plain baked apples. The tartness of the Golden Noble worked well in charlottes and pies. Only an astringent West Country cider apple sauce would cut through the fattiness of roast goose or pork.

Apples are perennial; after blossoming in spring they are gathered in autumn and ready for winter, when we can retreat to the kitchen and bake to our heart’s content. ‘Early-eaters’ like the Beauty of Bath and Laxton’s Early Crimson ripen in late summer. Soft and sweet they don’t keep long, but are the perfect foil for summer’s late blackberries. Autumn heralds the arrival of the ‘keepers’ like the Blenheim Orange, with its longer shelf-life and robust flavour. Eaten out of the hand, ‘late-keepers,’ with the longest storage time of all, bring a refreshing tang to the end of a long winter. Once you’ve munched on a crisp May Queen, the latest-keeper of all, you’ve reached the end of the season.

Apples have come a long way, from the forests of the Tien Shan Mountains on the borders of China (circa 8,000BC) via the Balkans and ancient Rome to Britain. Culturally, after years of recipe development and an ongoing love affair, we can rightly claim them as a national food. It seems, for the moment at least, that our apple industry is safe. Use it or lose it, as they say. An English apple a day keeps extinction at bay.

Recipes

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe