Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe

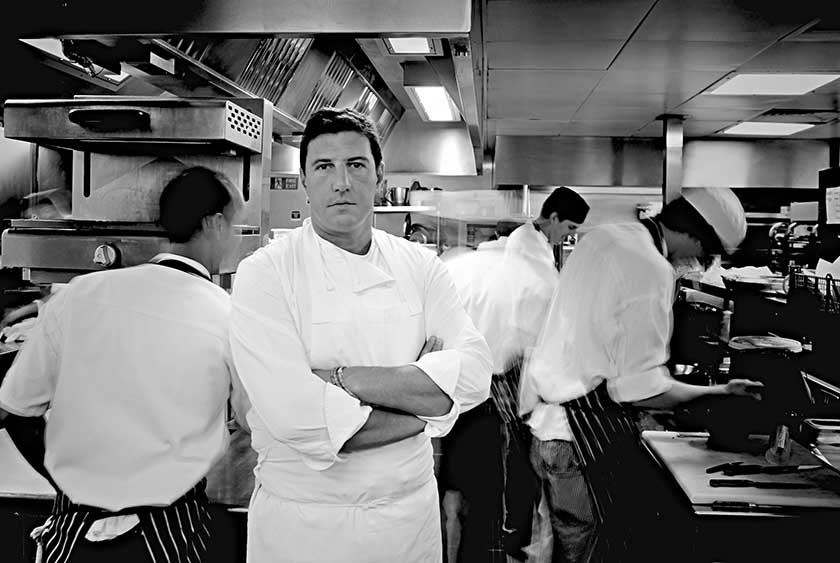

A giant in the kitchen and in stature, Claude Bosi tells Mark Sansom about his unplanned route from France to the pinnacle of the British restaurant scene

‘Finding your true cooking style is a bit like your sex life,’ says Claude Bosi with a lackadaisical Gallic shrug and tap of his aquiline nose. ‘You need to try a few different things before settling on a good one, you know?’ And Claude Bosi – a man who won a Michelin star a year after arriving in England without speaking a word of the Queen’s – certainly knows a heck of a lot about style on a plate. Regarding his sex life, Food and Travel couldn’t possibly comment.

I’m going to put my neck on the line and say that Bosi’s two Michelin-starred Hibiscus, right in the heart of Mayfair hedge-fund country, produces the best-looking plates in the capital. His use of colour and minimalism is closer to art than food, though that wasn’t always the case. ‘I used to cram the plate with too many elements, too much technique, too many flavours,’ he says. ‘It’s the curse of the young chef.’ Though with a culinary upbringing like his, you can’t blame him for drawing on every ounce of his learning.

A three-star education

He’s a rare breed of chef who knows what it’s like to be part of a kitchen that wins three Michelin stars. Before moving to England, he spent time working under the great Alain Passard at his restaurant L’Arpège in Paris. In the time he was there he saw the movement from one to two stars, and then two to three – the fabled stage that has eluded many of the world’s very best chefs. Though in his early twenties, Bosi didn’t realise how lucky he was. ‘It was all happening around me,’ he says. ‘I knew the team was very good but I probably didn’t know quite how good. They were pushing boundaries every day but I didn’t take it that seriously. Even then I didn’t really know if cheffing was for me.’

The fact that he claims he wasn’t treating it as earnestly as he could goes a long way to show the talent of the man. But then, restaurants were in his blood. Growing up in Lyon, the city widely accepted across France as having the best cuisine (even by Parisians), he was immersed in food from a young age. His parents ran a simple local bistro that drew on their mixed cultural heritage. ‘My grandma was from Sicily and Mum was Calabrian. Dad was born in Tunisia as his father was fighting in the war,’ he explains. ‘Though my family were typically French, in the way that at breakfast we would talk about what we were having for lunch and at lunchtime we would decide on the wine that we were having with dinner.’

School didn’t go brilliantly – ‘I wasn’t that bad, I just knew that it wasn’t for me’ – and aged 15, at the end of summer term, he was asked not to come back. ‘I wasn’t bothered, until my dad asked me what I wanted to do instead. Without thinking, I said I wanted to be a chef. I thought I’d have a nice chilled summer, then get a job in the autumn.’ He had forgotten that his father was immersed in Lyon’s food scene and found himself behind a stove by the end of the week.

‘I worked at le Brasserie du TGV in the station,’ he says. How does it compare to British station cuisine? You don’t have to be a Michelin-starred chef to guess his response: ‘Pfft. Different league. Food around transport here is a disgrace.

‘I was lucky at the brasserie. The chef there had once held a star and he gave me a great education. We were very busy and I learnt the importance of accuracy and consistency. I would look at the trains and want to travel. Lyon was never going to be me forever.’

Fast-track future

Forward to 1998 and another railway station, this time in the sleepy west of England. ‘I got off the train at Ludlow about 6pm,’ says Bosi. ‘It was pitch-black. The place was a dive. It was cold. I told myself that if no one picked me up by the time the next train came, I was going straight back to Paris. I had just come from working at Alain Ducasse, for God’s sake.’ However, a car did arrive. The Overton Grange Hotel’s general manager pulled up in a battered Mini Metro and Bosi crammed his hulking 188cm frame into the front seat without a word of English to his name. He saw a trip to England as an opportunity to learn the language and then extract as quickly as he arrived. Even after his stints with Alains Passard and Ducasse, he still wasn’t taking cooking seriously and didn’t know what he wanted to do for a full-time jo

The head chef at the hotel moved on a month later and in January 1999, Bosi took his job. In February the next year, he won his first Michelin star. The hotel owner subsequently had to sell and less than a year later, he found his first restaurant in Ludlow. He paid £40,000 for the 30-cover site, now called Mortimers, and set about crafting the style for which he is now adored. He opened in May 2000 and won his first Michelin star in 2001. The second came quickly after in 2003. ‘Things are getting serious now,’ he thought. He wasn’t wrong.

‘We did some great things in Ludlow. It was a proper kitchen,’ Bosi tells me. ‘I had Glynn Purnell [chef patron of one-star Purnell’s in Birmingham] with me when we got the second star. Me on the stove, him on the garnish and a talented Japanese guy doing pastry. There were only six of us in the kitchen and we took it as far as we could.’ But did he? The Michelin inspectors disagreed, as rumours of a third accolade spread like stardust but Bosi chose to roll up his knives and set out for London.

Discovering simplicity

‘I’ve never been able to sit still for long and I always wanted a piece of London. I met a guy who helped me find a site and we moved very quickly,’ he says. Though London wasn’t paved with gold. In 2008, on the day he opened Hibiscus, Lehman Brother’s went bust, sparking the global financial crisis. A week later, a bookies opened next door, then a week after that, a year-long scaffolding project started in the offices above his restaurant. However, Bosi took it all in his stride. ‘As we were a new business, we didn’t know any different and it’s good to work through hard times. There wasn’t much corporate business, sure, but we knew what we were doing was right and before long it was a success.’

Shortly after opening Hibiscus, Bosi travelled to Japan, a trip he credits as the pinnacle of his chef’s education. ‘It all made sense to me out there,’ he says. ‘The way they approach produce, the simplicity. I realised fig and foie gras, for example, are a perfect combination. A good chef needs to have nothing more than the confidence to put them together and season.’

His style is diametrically opposed to many popularist food movements from the past decade. Molecular gastronomy sits at the other end of the spectrum to Bosi’s beauty in simplicity and he doesn’t understand it. ‘If you have a fantastic piece of mozzarella, why would you want to blow it up? Why demolish beautiful produce to show off a technique? Food is food. Sometimes people think too much. At the end of the day, what is the point?’

An awful lot has changed in the 20 years that Bosi has called the UK home, not least in the way we approach food. ‘It’s been amazing to witness the evolution,’ he says. ‘Life is so hard but food makes you comfortable. It allows you to sit and relax. We are becoming more European. People are taking a lot more time at the table. When I arrived, it was like fuel in the car. British chefs are travelling more and bringing ideas back and the wine is now better than some in France,’ he says. I ask him to repeat that incase I misheard.

Now he’s looking to bring on young talent, working on projects like S. Pellegrino Young Chef of the Year, where he mentors the winners, something he clearly loves doing. ‘I tell them to eat in their restaurant once a month. You lose sight of what the food looks like on the plate. I tell them that following trends is dangerous. If you’re not Ferran Adrià, don’t try to be him.’ Trailblazing, in Bosi’s sense, means finding a style and making it your own.

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe