Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe

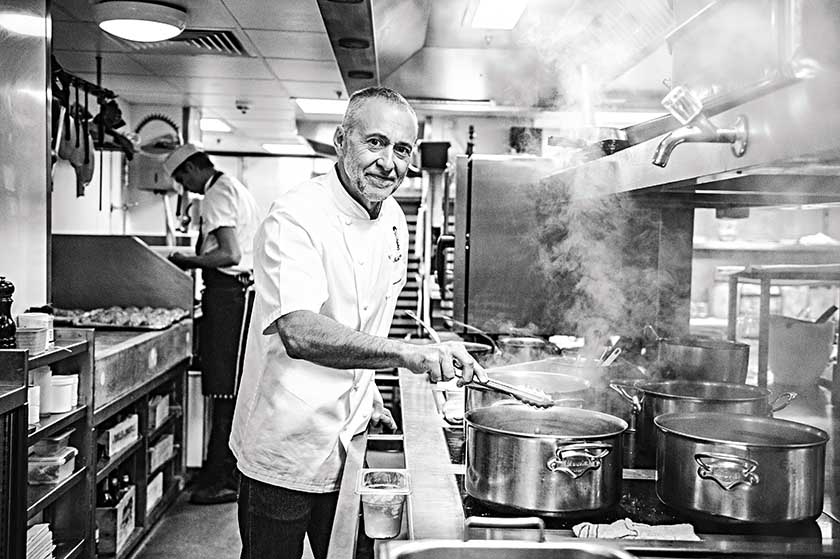

Michel Roux Jr never questioned that he would be a chef. But after 25 years running Le Gavroche his thoughts are turning to his successor, which is where the ‘best chef in the family’ comes in

A 29-year-old Albert Roux strides purposefully through a Kent field. His ferrets whip their way up his trousers and round his thighs in a tableau that is straight out of Last of the Summer Wine. Toddling along behind him, a four-year-old Michel Roux Jr chases the ferrets, sun rising on his back, as they make their way to the rabbit warrens. With nets applied to the holes, Albert looses the ferrets who scream down the subterranean labyrinth, flushing the rabbits into the grateful hands of the squealing boy. As the rabbits are trussed up and brought to the kitchen, the young Michel is returned to the playpen in his dad’s kitchen to watch Albert’s legs as he flits between stove and butcher’s block. Albert turns and tosses Michel a lump of puff pastry – there’s never been a call for Play-Doh in the Roux household.

Michel Roux Jr describes his early childhood growing up in Pembury, Kent as idyllic, and you can see why. Until Michel was seven, his father Albert was a private chef on the Fairlawne Estate. ‘Dad did the gardening, grew his own veg, reared rabbits, pigeons and chickens for the table,’ recollects Roux. ‘I went back to Pembury the other week and it’s not changed. The same village pub still sits at the top of the hill, and we actually did a gig for the local church the other month to raise funds for a new roof.’ It couldn’t be more of a countryside cliché if it tried.

Though in 1967, things changed for ever. Albert and his brother Michel (Michel Jr’s uncle) had their eyes on the ultimate prize. They opened a restaurant and had designs on making it the best in the UK, creating a dynasty of chefs in the process. Le Gavroche – the fulcrum of the family business – was born. It featured in the inaugural UK Michelin guide in 1974, gaining a second star in 1977 and a third in 1982, when it became the first restaurant in the UK to achieve the ultimate accolade. The restaurant brought authentic French cooking to the UK for the first time, and London lapped it up. Its menu was, and still remains, a bastion of classic French cuisine. Soufflés (both sweet and savoury) pepper the menu, while mousses, foie gras terrines and all manner of game are mainstays. The menu comes in French (bien sûr), while these days an English translation is provided. White-tuxedoed waiters present cloche-covered courses delivered on trolleys with no shortage of theatre. It’s a dining experience unrivalled in pomp and circumstance, and one that the Roux family have seen no need to change since opening.

As the young Michel played hide-and-seek in the enclaves and nooks the dark-wood and deep-red restaurant provided, he was never in any doubt where he wanted to end up. ‘I’ve never questioned that cheffing was for me. It’s always been there, always,’ he says without missing a beat. Even though he knew he would end up installed behind the family pass, he knew he needed to widen his sphere of experience. First, he worked at Charcuterie Mothu in Paris and then the Mandarin Hotel in Hong Kong, before returning to London and La Tante Claire. He was there a matter of months before his father called and told him he needed cover on the pastry section at the family restaurant in 1991. He’s been there ever since.

Roux’s first few years at Le Gavroche weren’t the easiest. One year after taking the reins, the Michelin guide docked its third star. His vision was to marginally change the restaurant’s ethos for the better, and the Michelin inspectors didn’t agree, but in typical Roux fashion, he looked for the positives: ‘There was a transition period in the early Nineties. I viewed it as evolution, not revolution. My key tenets were to lighten up the menu – a lot less cream and butter and no more thick, heavy sauces. No more liaisons, no more flour.’ For a restaurant that made its name in classic French gastronomy, it was a sizeable departure from the prototype he had been handed. ‘But losing a star didn’t do any damage to the business. If anything it boosted trade, as customers came in to see what the hell was going on.’ It may have looked okay on the balance sheet, but what did the restaurant’s founder think of the deviation?

‘In the early days, father still had a big influence. It wasn’t the easiest of times and it was hard for him to let go, as it would be for me to now.’ The way he says it suggests fractured times for the family. With the apron strings well and truly cut, does Albert have a say now? ‘He would if he could! He doesn’t pop into the kitchen any more as he has trouble walking, though if he was still mobile he’d be at the end of the pass watching the dishes as they come out. Nowadays he just comes in for a free lunch three times a week. Wouldn’t you?’ As I watch the morning delivery of bright-hued vegetables make their way through the restaurant, and get a scent of the marrow-heavy stocks that have been simmering all night, I have to agree that I would. Whatever changes he chose to instill were certainly best for the restaurant – and the family.

Now, as Roux celebrates 25 years at the helm he’s ready to prepare the succession. His daughter Emily has just turned 25 and – believe it or not – has a better cooking education than any of her patriarchs. ‘Emily always said that she wanted to be a chef. We looked at various catering colleges and she chose the Paul Bocuse School in Lyon and did three years there. She went on to do placements in Paris (at restaurant 39V) and in Monaco (at La Trattoria). She then returned to Paris for 18 months at Akrame, a seriously up-and-coming restaurant that majors in modern techniques. She’s seen and learnt a lot.’

In a family with so many celebrated chefs, how do they decide who cooks the Christmas lunch? ‘Well, we all have fairly big egos, and I don’t think any one person runs it – we all think we know better. But the one thing that brings us together is the desire for perfection and to get things right. We may take a different route to get there, but that’s always the endgame.’

Will he be drawn on who’s the best chef in the family? ‘That would be my daughter,’ he says after a long pause. ‘I’ll let her have that – she’s certainly more au fait with modern techniques.’

As Roux’s star has grown, so has his persona on television. A spat with the BBC over his outside interests led to him no longer appearing on MasterChef, disappointing women up and down the country. When I mention that my mother describes him as the ‘thinking woman’s Gordon Ramsay’, he bellows with laughter. ‘I don’t know whether to laugh or cry at that one. Yes, I’ve heard that kind of thing before. There might be some women – and men – who go weak at the knees sometimes, it’s a lovely compliment.’ It’s no accident that Roux looks good on screen. His love of fitness and marathon running are well-documented. He uses pounding the streets as time to focus his thoughts on new plans for dishes and recipes. ‘I love the freedom running brings. Even though my knees are giving me jip, I’ve not hung up the trainers just yet. I’d still like to do the Marathon des Sables [a 251-kilometre ultra marathon in 50C temperatures through the Sahara desert], so I still have goals. Just look at what Eddie Izzard’s done; he’s hardly the fittest of people.’

As he does in the kitchen, Roux is forever looking to the future. He’s a non-executive director on a huge-scale project in which a disused underground tunnel in Clapham, south London, is used as a grow site for restaurant produce. ‘Growing Underground, as we’ve called it, is a look into how we’ll be eating in years to come. It uses a 36m-long tunnel to grow pea shoots, amaranth, mustard cress, micro basil and all manner of shoots and leaves using state of the art LED lights and hydroponics. There’s far fewer miles transporting it to restaurants – it’s local produce at its most pure.’ But won’t flavour be affected by a lack of terroirs or direct sunlight? ‘No. The majority of herbs are grown in polytunnels with artificial light and soil – it’ll taste as good as the watercress grown in Hampshire.’

As keen as he is at pushing boundaries in terms of produce and technique, Roux still believes traditional cheffing has a place. ‘I’m often getting CVs for sous chef positions from kids aged 20. I think: “hang on a minute mate, you’re wet behind the ears,” some guys will have grafted for decades before they feel ready for that kind of job.

‘As restaurants are opening like mad at the moment, there’s a shortage of qualified chefs. Wage demands are too high and they’re being pushed up by agencies – it’s turning into the situation you see in football clubs. Agents have no qualms in ringing around London to find a pastry chef.’ Does that mean he thinks that British chefs are coming into the business with expectations greater than their station? ‘Take my kitchen for example. Most of my staff here are from Italy, Spain, Portugal, and very few English. It’s a mixture of wages and propensity to do the work.’

Roux still regularly clocks 16-hour days, although for the first time in the restaurant’s history, Le Gavroche in Mayfair, west London is now closed on Sundays and Mondays. ‘I’ve cut the hours so everyone gets proper rest days. We now have one team who work together all week – when we were open six and a half days, the rota was mad. Kitchen dynamics have changed.’

As the star of the celebrity chef has come vividly into focus, kitchens have become a glamour industry, though one without the glamour. Many chefs and restaurant owners have adopted their own take on man management and Roux is no different: ‘I’ve never believed screaming, shouting and pushing was the right way with people – though I know there are still some dinosaurs out there. Of course, I lose my rag sometimes.

‘I accept that someone doesn’t have the skill and might make a mistake when cooking a piece of steak, but you need to get over it and learn. It’s things like lateness, not being clean, and not respecting produce that really drives me mad.’

While Roux looks to the future in many respects, he’s old-school at heart. There are some elements of modern gastronomy he doesn’t understand or even, indeed, trust: ‘Fermentation I just don’t get. I don’t like the taste. It seems every menu in London has something fermented or pickled. I worry as, in the wrong hands, it can be extremely dangerous.’ You only have to remember what happened in 2013 when 70 guests at three-time World’s Best Restaurant Noma in Denmark suffered from food poisoning.

As he talks about his plans for the future, a six-strong film crew files into the restaurant and heads downstairs to the kitchen to set up. It’s barely 9am and Roux will have completed his second interview of the day before lunch service starts. With the same glint in his eye now as you see on television, you get the impression he’s a long way from relinquishing the reins just yet.

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe