Apricots

Their window of ripeness is tricky to pinpoint, but get it right, says Clarissa Hyman, and this subtle, delicate fruit can lend a sensual allure to both sweet and savoury dishes.

Apricots are the best of fruits, and the worst of fruits. An under-ripe apricot is a vile thing: hard, sour and acidic. Eating one is like snacking on a canary yellow golf ball. The very thought makes my stomach wince in gastric protest. Unfortunately, apricots are delicate travellers. Although soft and tender when sun-ripe, they are often transported under- ripe. Picked, on the other hand, too late, and the flesh either spoils or becomes flabby and floury. But if you are lucky enough to find some fine fruit that are luscious, perfumed and as glowingly beautiful as a titian maiden, well, that’s quite a different story. one that began thousands of years ago in the mountains around Beijing…

The history of the apricot may be long, but its spread has been slow, perhaps because of its sensitive temperament and particular needs – a temperate climate with a cool winter but no frost or strong wind during the early blooming period. drought, too, is another enemy of the tree. Nonetheless, the fruit was believed to have been grown in the hanging gardens of Babylon, and was known to the Greeks and Romans, although whether they cultivated them or imported them remains unclear.

The scientific name for apricots is prunus armeniaca, which seems to suggest an erroneous belief that they were a kind of plum that came from Armenia. An alternative name of the time, persica praecocia, could be taken to mean ‘the early-ripening Persian fruit’. It is possible that this gave rise to the similar-sounding word ‘apricot’ but no one is sure: the name we have today is a linguist’s nightmare, with many possible origins and references.

The fruit trees largely disappeared from Europe until the Moors planted them in Andalucia. They reached California early in the 18th century, probably introduced by the missionary fathers. The classic variety, blenheim, is still superb but when the groves had to move from Santa Clara further east, the land proved less suitable, and inferior varieties have come to dominate. In England, Lord Anson at Moor Park in Hertfordshire in the 18th century had considerable success with a variety called moorpark that is still grown today. Commercially, however, the largest producer in the world is now Turkey, followed by Iran and Uzbekistan.

The 19th-century writer John Ruskin described the apricot as ‘shining in a sweet brightness of golden velvet’, an exquisite phrase that captures the fruit’s matt bloom and sensual, subtle oriental allure. The small, blushing fruit, neither orange, red nor yellow, is a delicate fusion of all three colours: sun-speckled or with rosy patches, picked warm off the tree, it has an incomparable taste.

The Oxford Companion to Food describes a ‘great apricot belt’ as stretching from Turkey to Turkestan. Within this region, there is a huge diversity of fruit, ‘white, black, grey and pink apricots, from pea- to peach-sized with flavours equally varied’. Near-translucent white apricots are much prized in the near east and are said to be of supreme delicacy and sweetness. a California grower, Ross Sanborn, spent 40 years breeding white apricots from a small bag of seeds that made its way from Iran to the US in the 1970s.

Many varieties, however, have lost their special character as a result of growers favouring size and appearance over taste, resulting in poor textures and insipid flavours. French apricots remain among the finest, especially from Roussillon, Provence and the Rhone. In California, popular hybrids have been developed such as the plumcot, which has a velvety purple skin, scarlet flesh and a classic apricot aroma; and the yellow-skinned and pink-fleshed aprium. Another Californian hybrid, the trade- marked Monster Cot, is as big, brilliant and super-sweet as its scary name implies.

Given the transportation problems, many apricots are canned, although the process seems to add little to their charms. Another alternative is drying, but while this neon-coloured fruit of Iran, Australia and California is cheap, it tends to have a rather insipid, sharp taste. Most dried apricots, unless organic, are also treated with sulfur dioxide (E220), which acts as a preservative.

The muscat flavour and lush texture of the large, dark fruit grown in the Malatya valley in Turkey is well worth the hunt, and although the dried, beige hunza apricots from Kashmir look small, hard and wrinkled, they possess an intense caramel taste. left to dry on the tree before harvest, they are said to contribute to the longevity of the region’s inhabitants. Thin sheets of dried ‘apricot leather’ are also popular in Turkey and Syria and have a concentrated flavour.

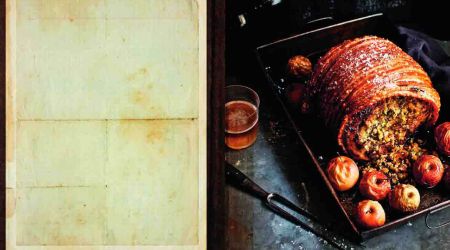

Apricot jam comes into its own with buttery croissants or used in confectionary for fillings, glazes and sweetmeats. Almonds are a natural partner, and both the dried and fresh fruit are widely used in Middle Eastern cooking to give a ‘sweet-sour’ dimension to rich, savoury lamb dishes. The chef Tom Kitchin suggests balancing the richness of duck breast with a compote of red onion, Szechuan pepper and dried apricots.

Poached, fresh apricots make the best glazed fruit tarts, or they can simply be served as they are in honey and lime juice. Even the apricot kernel plays its part in adding a nutty edge to brandies and liqueurs; it is also traditionally used to flavour Amaretti di Saronno biscuits from Italy.

Apricots are widely valued for their health- giving properties. They are rich in mineral salts, including phosphorus and magnesium, and also in carotene, especially when the fruit is fresh and ripe. Finally, with a high fibre to volume ratio, a couple of apricots a day allays – excuse me for mentioning it – constipation. Okay, Ruskin woudn’t find that very romantic, but it sure as hell works.

Recipes

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe