Pumpkins

Rich, earthy flavours and smooth, melting flesh – these heavenly fruits are for more than just Halloween. Clarissa Hyman gives us the lowdown

Fluorescent orange pumpkins, carved into toothy, zig-zag grins are the symbol of Halloween, but you wouldn’t really want to eat one. By all means disembowel and gouge out the flesh and stick a candle inside so the light flickers through the demonic incisions, but these bland, super-sized globes are best left for ghastly ghouls and wicked witches.

When it comes to pies and soups, stews and curries, my advice is to seek out smaller varieties that offer glowing Van Gogh colour, dense but melting texture and an earthy, rich taste. Pumpkins are blood brothers to marrows, squash and gourds. Names and definitions overlap and are often interchangeable, but all belong to the family Cucurbitaceae and the genus Cucurbita within it. The leading species are Cucurbita pepo and Cucurbita maxima but, as The Oxford Companion to Food notes, ‘The genus poses intractable problems of nomenclature.’ I advise against further study unless you want to end up with a headache as big as a Halloween pumpkin.

There are hundreds of varieties and they come in all shapes, colours and sizes. When it comes to identification, there is considerable crossover with squash. Even in 1867 Lady Llanover, author of Welsh cookery book The First Principles of Good Cookery, wrote: ‘The varieties of this plant are so numerous that it would be beyond the limit of any cookery book to attempt an enumeration of comparative merits.’

Pumpkins are notorious for the triffid-like growth of their vines, although there are some short-vined varieties that suit a small garden. They are harvested when fully ripe, then left in the sun so the skin can toughen and dry out; provided the skin is undamaged, whole fruits can then be stored for several months in a frost-free, cool place.

Some of the best varieties include long-lasting, versatile Crown Prince, little Sweet Dumplings that can be stuffed and roasted whole, and Muscade de Provence with green-orange skin and moist, delicate flesh that hints subtly of melon. Baby Bear is a medium-sized pumpkin with a dark green stalk, excellent for pie and cakes. Queensland Blue has a thin, greyish skin and a good texture when cooked. As a general rule, the larger the pumpkin, the less flavour the flesh will have. When buying them, look for hard, heavy fruits with no blemishes.

There is no way to approach a bulging, bosomy pumpkin gracefully, but once you steel yourself to wield the first blow and hack through the tough, ribbed skin as though cutting through jungle growth, many possibilities open up. Pumpkins tend to be watery and disintegrate easily, so one of the best ways of cooking them is to roast thick wedges on their skins, drizzled with olive oil, and herbs or spices: the skin and seeds then come away easily from the flesh. Roasted chunks are also particularly good with game – which is in season at the same time – or the flesh can be mashed into a purée.

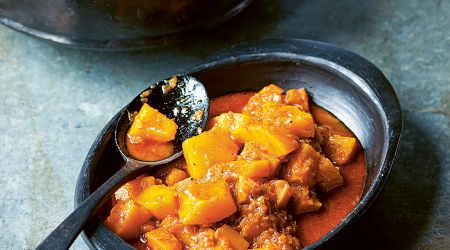

Alternatively, fry cubes with garlic, pine nuts and fresh coriander, or pack into a pan with just a splash of water, cover and cook over a low heat until tender. Arthur Potts Dawson suggests an excellent gratin with cheddar cheese, white wine and thyme; one of Skye Gyngell’s favourite pickles is made with pumpkin, coriander and fennel seeds, lemon thyme and chilli.

Give a velvety, golden pumpkin soup a cutting edge treatment with ginger and garlic, or pair with chestnuts, bacon and sage for a warming broth. Add to a spicy casserole with beans, mushrooms, sweet potatoes, sweetcorn and chillies. Stuff ravioli with pumpkin, sage and pecorino, or bestow a medieval Italian air with the intriguing but effective inclusion of crumbled amaretti. Risotto with pumpkin and sage is another north Italian classic, while in Cyprus, pasties are stuffed with pumpkin and crushed wheat flavoured with cloves, cinnamon and raisins.

Of course the fruit plays a traditional part in American Thanksgiving, but pies made with fresh pumpkin, eggs, cream, brown sugar and gingerbread spices are as different from canned pie filling as Venus is from Mars. Some Americans, however, will insist on the latter, though that gets into complicated nostalgia territory.

Pumpkin seeds, which contain a good percentage of oil, are washed, dried and salted for eating. There are even special varieties bred for their seeds that are without a hull and can be eaten whole and unshelled. They make an addictive snack. At Riverside Farm in Devon, the recipe for Thai Pumpkin Soup uses the otherwise discarded fibre and seeds to make a great stock. Amber pumpkin seed oil has a fabulous, nutty flavour that is better used as a condiment than as a cooking oil. It is a speciality of Austria and Slovenia, where records of its production date back to the 17th century. It is made by pressing the roasted, hulled pumpkin seeds from a local variety of pumpkin, the Styrian Oil Pumpkin. Splash it, for example, over roasted wedges or into a risotto just before serving, or even add a few drops to vanilla ice cream.

And let me know if you find a beautiful, round, magical pumpkin that turns into a carriage fit for a princess. I’ll bring the glass slippers. Just try to make it away from your ball before midnight.

Recipes

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe