Rocket

Hailed an aphrodisiac by the Romans, rocket was rediscovered as the sexy salad leaf of choice in the Eighties. Clarissa Hyman explains why she loves the peppery plant with recipes by Linda Tubby and Christine Manfield

If sexual intercourse, according to the poet Philip Larkin, began in 1963 then rocket and sexy Italian food were surely creations of the 1980s. Not that either la dolce vita or the spiky green salad leaves were unknown before that time, but until then a seductive dinner for two meant a plate of spag bol and a bottle of chianti with a candle in the top.

In the no-holds-barred climate of the 1980s, however, the British discovered aspirational food, culinary style, power lunches and gastro porn. And, rocket played a key role. Its home-grown counterpart, watercress, seemed by comparison virtuous and parsonage provincial. Rocket, on the other hand, was the equivalent of Euro-trash: racy, exotic, sophisticated. Especially when you called it arugula in Italian-American movie-speak. It may have been something Italians took for granted, but it burst upon the British scene like shoulder pads and disco dancing.

This small plant however has a long history. It was one of the first plants to be cultivated in the Middle East between 9000 and 7000BC. It originated as a weed, along with rye and oats, but became a crop as grain cultivation spread further north. By the time of the Romans, rocket was valued not just for the spicy, mustardy leaves but also for the seeds which were used to flavour oils.

Rocket, however, was not just a popular ingredient but was also considered an aphrodisiac. It was sown around the base of statues of Priapus, a figure of considerable endowment, and believed to be what can only be described as the original Viagra. The Roman gourmet Apicius ground the leaves in aromatic salts to use as a flavouring for wild boar and grey mullet, and also included the seeds as part of a sauce for boiled crane in a typically lavish classical example of conspicuous consumption.

Rocket’s salacious reputation probably accounts for the fact that the plant was subsequently frowned on by the early Christian church. Numerous writers of the time spoke of its ‘hotness and lechery’ and it was banned from monastery gardens with the result that rocket practically disappeared from Britain’s gardens and tables for almost 300 years.

When rocket was ‘re-discovered’ 20 years ago, it became the height of culinary fashion, but since then its staying power has been based on its genuine, delicate, peppery charms. The tender, dark green and serrated leaves have become a regular, indeed ubiquitous, part of our daily dining routine. Its distinctive taste makes it an excellent addition to a wide range of salads, sandwiches and appetisers, either on its own or combined with blander, sweeter leaves.

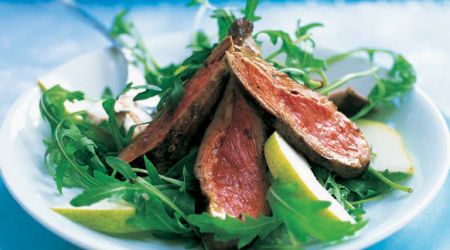

Rocket has considerable versatility, scattered on pizzas and tarts or as a foil for grilled goat’s cheese on toast, or paired with feta or brie. In Italy it is often served with carpaccio, thin slices of raw beef and shavings of Parmesan drizzled with olive oil. The combination with Parmesan may have become a culinary cliché, but one of the world’s best sandwiches is composed of rocket, Parma ham and slices of Parmesan in focaccia or sourdough bread. Blend with garlic, Parmesan and pine nuts to make a pesto-style sauce for pasta, risotto or potatoes, or cook quickly in olive oil or butter, then stir the just-wilted leaves into a bowl of pasta. Try it also alongside roast beef or grilled steak.

In Italy, and also in other countries of the Mediterranean and North Africa, you can find rocket growing in the wild. However, the ‘wild’ rocket we now buy in expensive packets is somewhat of a misnomer. It was in the 1990s that nations including Italy, India, Egypt, Turkey and Israel pooled their native strains to develop varieties that include cultivated ‘wild’ rocket. Compared to ‘non-wild’ cultivated rocket, usually described as salad or ‘sky’ rocket, the small, dark leaves have a more intense, peppery flavour.

Rocket, however, is a relatively easy, cut-and-come-again annual salad leaf to grow in British gardens. And rocket it does, too. You can sow the seed and watch it crop within a month. Successive sowings from early March are a good plan, but thin the seedlings and use them as soon as possible. Cut back the leaves as they grow, or the plants will quickly go to seed. The small white and yellow flowers are also edible and decorative to scatter over a salad. Freshly picked leaves are rich in antioxidants, but many in ready-washed packets have been drenched in chlorine; if possible, try to buy leaves that have been washed in spring water.

There can be few lovelier lists of ingredients than the Renaissance spring salad described by Giacomo Castelvetro in 1614 which includes, ‘the tenderest leaves of borage, the flowers of swine cress, the young shoots of fennel, leaves of rocket, of sorrel, rosemary flowers, some sweet violets, and the tenderest leaves or the hearts of lettuce.’ Fresh, healthy and exquisitely pretty, it is a dish we would happily eat today. Rocket may have had a chequered culinary history, but it is more than a modern food fad or historical curiosity. It is one of the stars of the salad garden, and a simple, leafy delight that is back to stay.

Recipes

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe