Food and Travel Review

You could drown in crème double in the Fribourg region. It would be a soft, sweet end, a tilt forward into one of the wooden bacquets from which the speciality of the canton is served. But without the cheesemaking for which the area, particularly La Gruyère, is famed, there would be no cream to drown in.

Gruyère means three things, and although the spelling must be attended to, it is a pleasant lesson to learn. La Gruyère is a district of the western Swiss canton Fribourg, characterised by its Pre-Alp landscape and quiet, friendly villages. Gruyères is the lovely medieval town which pops up, picturesquely, in many of the area’s vistas. And Le Gruyère is the cheese which, despite also being made elsewhere, is an expression of the land, culture and tradition of this place; something which is considered extremely special.

Le Gruyère AOC, made with equal parts raw milk and pride, has been produced here since the 12th century (the classification came later, of course). Originally, it would all have been made in the high alp huts (calling them chalets suggests an exaggerated level of grandeur) amid the summer pasture, where cattle and farmers decamped during warmer months. In the 19th century, the advent of village dairies meant that the cheese could be made on the plains below, all year round, in greater quantities. The alp cheese – look for the notation ‘d’alpage’ – now forms a tiny fraction of production, but in the canton of Fribourg it’s gratifyingly easy to find, which makes the labours of cheesemakers like the Piller family worthwhile.

Days after descending from the Pillers’ alpine hut at the top of the 1,617m Vounetz mountain, I still catch the scent of woodsmoke about my person. To visit their basic summer home, where three generations live above the quarters of their 52 Holstein cows, we’ve taken a cable car from the village of Charmey. In the winter, it’s a modest ski ‘resort’; before the snow, it’s a great place to start a walk. But the Pillers are too busy for leisure. Béat, who has been making cheese since he was 16, is up daily at 4.30am. Skimming that delicious crème double off the milk is one of the first jobs in the two-room dairy, known as a trîntzabyô in the patois that’s still spoken alongside French. Then, over the fire that fills the room with smoke and perfumes the cheese, the raw milk is heated in an 850-litre copper pot, starter and rennet added, the curds cut and the contents warmed to a steaming 55°C. After cooling his arms with cold water, Béat braces a cheesecloth and boldly leans in to catch the curds that will form the first of today’s three cheeses. Deftly transferred to a large ring mould, the curds are tied with a topknot, to be pressed, turned and brined, turned again and brushed with salt, and, a few days later, taken down the hill to a cave for maturation.

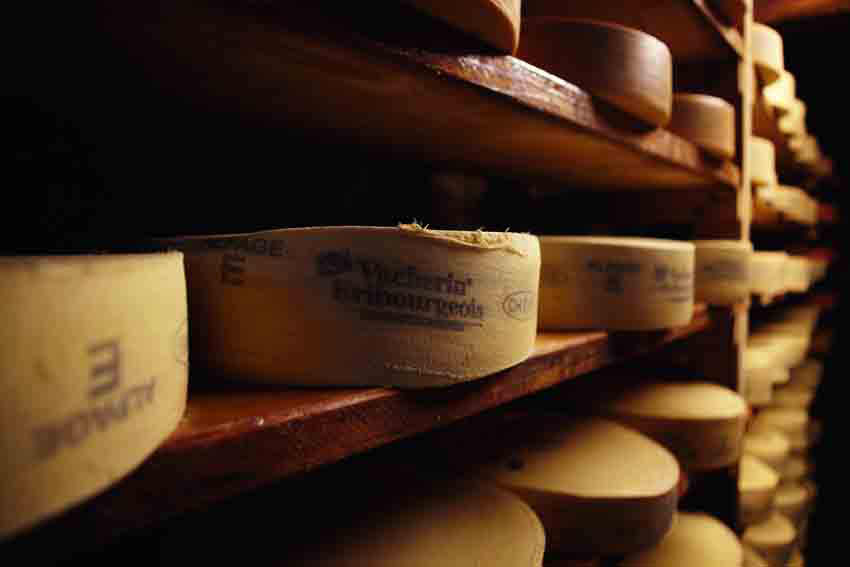

The Pillers also make a softer, round-flavoured Vacherin – of which more later – and a few much smaller rounds of fresh, light Sérac. ‘It’s the smoke and ambience of the trîntzabyô, the flavours and flowers in the grass, and even details such as whether the mountain has sun or not, which makes the alpine cheese special,’ says Béat. ‘Every cheese is different.’ There are around 30 alpine huts making Le Gruyère d’alpage AOC, but Béat’s wife Florence, who gave up her job in a pharmacy to follow him up the mountain, reckons he could pick one of his own out of a line-up.

A great place to test this theory would be at Bulle’s Thursday market. In summer, there are added attractions – alphorn music and craftspeople – but there’s food all year round. Bulle is the capital of La Gruyère, famous for its cattle fairs; its flag is a red bull on a white background, suspended above the characteristically wide main street. There’s a 13th-century castle (now the police station) and a museum stuffed with the folk art we see everywhere. Marguerite Raemy was a cheesemaker before she started selling her poyas, the naïve paintings of cows and cattle farmers (known as armaillis) making the annual transhumance to the alp fields. Like many people we’ll meet, she cites tradition and authenticity as the precious elements of the region. It’s not fair to call it insular – further into the market there’s a stall selling sugar cane and coconuts – but it’s certainly traditional. Our guide, Carina, bumps into a neighbour at the market. Paul is a member of Les Barbus de la Gruyère, guardians of local tradition. He is wearing the tough, traditional working dress, the bredzon, including a shirt with the delicate pale blue edelweiss pattern that is used everywhere from babygros to canvas pumps. It is accessorised with a hat, an initialled manbag, a walking stick, and an extravagant white beard. Paul is totally rocking it.

Later, from the terrace of one of the restaurants in Gruyères, we see the alphorn players from Bulle leaning their long, rather over-manly instruments against a wall – a serene moment before they play a local concert. They head up towards the top of the town (founded in 400AD by the vandal king Gruerius, who took his name and coat of arms from a crane flying against a red sky) toward the well-preserved medieval castle. Once home to the leaders of Fribourg, it’s now owned by the canton and a grand setting for contemporary art and sculpture. The pedestrianised village, with its geraniums and fountain and glimpses of the alpine hills beyond the streets, is bewitching. Visitors mostly come for the day; we stay overnight to take the time to be bewitched in relative peace.

That night, we taste the first of many fondues. Fribourg’s most famous dish is the moitié-moitié fondue, made with half Gruyère, half Vacherin Fribourgeois. Served with chunks of bread or new potatoes, it is both powerful and addictive, clinging to the bread until we come to the toasty film, known as the religieuse, at the bottom of the pot. Our guide, Carina, who is recognised everywhere we go because her father is both a dairy farmer and a champion Swiss wrestler, suggests we also try the all-Vacherin fondue. Good Vacherin (ideally d’alpage) is softer than Gruyère, with a lively, multifaceted flavour; mushrooms, grass, cowsheds.

The best thing to do before eating a traditional lunch here is to miss breakfast. We take a short hike up from the outskirts of Pringy village to Buvette Les Mongerons. It’s all uphill, but the views over Gruyères are green and pleasant, and signposts hint that we could walk further if it wasn’t for the temptations of lunch. At Les Mongerons Odile, Pharisa cooks mountain specialities in a tiny kitchen; the cows, housed on the other side of the wooden partition, have considerably more space to graze than she does to whip up her alpine dishes. No-one knows when pasta came to Fribourg, but it’s become a staple of chalet cooking, which is mostly reliant on the storecupboard and the produce of the trîntzabyô. We try some steaming bowls of soupe de chalet, made with milk, crème double, tender macaroni and potatoes, and the merest suggestion of greens courtesy of leeks and wild spinach. Sprinkled with Gruyère to serve, it’s salty and rich. Also on the menu is macaroni de chalet, cooked with onions, crème double and Gruyère; we watch in admiration as a slender woman in dashing red trousers finishes off a plateful, with smoked ham and sticks of Gruyère, before directing a spoon towards the classic local dessert – crisp meringues with more crème double. We roll happily back down the hill.

With produce of this quality, eating is never a hardship. Nevertheless, it’s starting to feel as if it’s time for a vegetable. It’s lovely to sit by the window at Frédérik Kondratowicz’s Restaurant de l’Hôtel de Ville in the city of Fribourg and be brought a salad strewn with edible flowers, followed by roast chicken with a vibrant herb sauce, served with more vegetables than we can count. Kondratowicz loves Gruyère cheese too much to cook with it, preferring to let patrons enjoy it neat, from the impressive cheese trolley. He keeps a variety of ages, some made by the father of one of his apprentices; the 24-month-old tastes like a cross between parmesan and cheddar. But he does cook with the other produce of the region, and on the whirlwind market tour he makes every Saturday, Frédérik picks up dark-crusted bread made with an old wheat cultivar, Rouge de la Gruyère, and local organic vegetables, salad, fruit and flowers. There is the mouthwatering jambon de la Borne, smoked like so much local meat in a chimney, then given a basting with honey and orange juice and sliced hot from the spit. We also try gâteau du Vully, a sweet flan made with a brioche-style bread base and filled with double cream and sugar, then baked dotted with butter. It’s named after Mont Vully, on the banks of Lac de Morat, where small vineyards produce the chardonnay, syrah and cabernet franc – all good – that we’re offered on our travels.

On the market, the sound of French being spoken is slightly louder than the sound of Swiss-German. Fribourg is the capital of the canton, north of La Gruyère. Following its founding in 1157, it came under the control of a succession of Hapsburgs and Savoys. Its bilingual status was the inevitable consequence, and it’s also well known as a Catholic city, with nine convents and monasteries and many theology students. Laid out over three levels, with the new opera house at the top and the well-preserved old town at the bottom, it’s ideal territory for wandering. We’re amazed to see a bus rumbling over the covered wooden Bern bridge, originally built in 1653. Here, the Sarine river, once key to the leather tanning industry and the export of linen (and cheese), bends sharply; it’s difficult to remember which side you’re on.

You can’t talk about food in Fribourg without talking about la Bénichon. Originally connected to the consecration of the church, it’s an autumn farm feast and festival that is now linked to harvest and the descent from Alpine fields. Each town has a set date for their own celebration, but many of the goodies that are traditionally eaten as part of Bénichon are available all year round. As a farewell gift, Carina has bought us a little picnic of the specialities that usually begin and end the meal. Cuchaule, an enriched bread flecked with saffron and spread with sweet-spicy moutarde de Bénichon, comes first. Then there are bricelets, little tuiles made on a pattered hotplate, which look plain but taste wonderfully buttery, light finger biscuits known as croquettes, and pains d’anis, speckled deliciously with aniseed. We crunch contentedly, but then we realise that something is missing. Where’s the crème double? The answer when in canton Fribourg is, of course, that it’s everywhere.

Where to stay

Prices are per person, per night and include taxes, unless otherwise stated.

Le Vieux Manoir A small, elegant hotel on its own stretch of Lac de Morat shore. The star spot is the private Glass Diamond suite, set on stilts in the grounds, but all the individually-decorated rooms are stylish and comfortable. Modern Asian and traditional Swiss cuisine can be found in Restaurant Juma and in La Pinte de Meyriez. Doubles from £195, including breakfast. Rue de Lausanne 18, 3280 Murten-Meyriez, 00 41 266 786 161, http://vieuxmanoir.ch

Best Western Hôtel de la Rose A business hotel in the heart of Fribourg, the Hotel de la Rose is friendly and brilliantly situated for early starts at the market, just across the street. Double rooms from £65, including breakfast. Rue de Morat 1, 1702 Fribourg, 00 41 263 510 101, http://hoteldelarose.ch

Hostellerie Des Chevalliers Tucked just outside Gruyères proper, this simple hotel is a great base. Some rooms have balconies overlooking the mountains, with tinkling cowbells completing a wonderful cliché. Doubles from £105, including breakfast. Ruelle des Chevaliers 1, 1663 Gruyères, 00 41 269 211 933, http://chevaliers-gruyeres.ch

Travel Information

The currency in La Gruyère is the Swiss Franc (£1=1.50CHF). Fribourg is one hour ahead of GMT. This pre-Alps region enjoys summer temperatures over 20˚C whilst winter’s snow provides excellent skiing.

GETTING THERE

Swiss International Airlines (http://swiss.com) flies direct from London Heathrow and City aiports to Geneva.

Easyjet (http://easyjet.com) flies there directly from Gatwick, Luton, Manchester, Leeds, Bristol and East Midlands.

Book trains to La Gruyère from Geneva at http://rail.ch.

RESOURCES

Fribourg Region (http://fribourgregion.ch/en) provides plenty of information to help plan your visit to La Gruyère and the surrounding area.

Switzerland Tourism (00800 100 200 30, http://MySwitzerland.com) is a great resource for more information on the country.

FURTHER READING

Cheese: Slices of Swiss Culture by Sue Style (http://bergli.ch, £35) will help you to discover the best cheese made in Switzerland, including some of the most creative cheese-masters in remote destinations.

Where to eat

Prices quoted are per person for three courses and half a bottle of wine.

Buvette Les Mongerons Arrive on foot at this alpine chalet, where mountain specialities use macaroni, cheese and crème double. There are great views over the valley from the terrace, and a cosy, traditional back room. Walking route signposted from parking places on the Route de Moléson between Pringy and Moléson-sur-Gruyères, from £13. 00 41 269 212 239, http://mongerons.ch

Restaurant de l’Hôtel de Ville There are views over Fribourg from the balcony at Frédérik Kondratowicz’s relaxed restaurant, which serves instinctively-cooked dishes with local ingredients and a slight Mediterranean inflection. At lunch, the formule is incredibly good value for seriously accomplished cooking. Set lunch £18. Grand Rue 6, 1700 Fribourg, 00 41 263 212 367, http://restaurant-hotel-de-vil...

Restaurant Juma (see also Where to stay) Fish from Lac de Morat is a key ingredient for chef Franz W Faeh at Le Vieux Manoir’s smarter restaurant. The dishes are light and complex, reflecting his time spent in Asia. Time it right and you’ll get a stunning lake sunset thrown in. From £52. Rue de Lausanne 18, 3280 Murten-Meyriez, 00 41 266 786 161, http://vieuxmanoir.ch

Le Pérolles An unpromising stairway leads down to Pierrot Ayer’s Michelin-starred, smart-but-friendly restaurant. The cheese ‘chariot’

– far grander than a mere trolley – offers some real Swiss indulgence beyond Gruyère. From £50 at lunch. Boulevard de Pérolles 18a, 1700 Fribourg, 00 41 263 474 030, http://leperolles.ch

La Pinte des 3 Canards Just outside Fribourg in the close-walled Gottéron valley, this simple, atmospheric restaurant juts out over the river. Try the salad of trout, which is farmed, caught and smoked further up the river. From £20. Chemin du Gottéron 102, 1700 Fribourg, 00 41 263 212 822, http://pintedestroiscanards.bl...

Food Glossary

- Bricelets

- Delicately patterned waffle-style biscuits, enriched with cream.

- Cuchaule

- with saffron and decorated with a cut-glaze pattern, this traditional Bénichon bread is found on many breakfast tables, too.

- Crème double

- The cream skimmed off the local milk is so rich that it stands up in soft peaks by itself. It’s served with meringues and used in rich chalet dishes.

- Fondue moitié-moitié

- Half-and-half fondue made with Vacherin and Gruyère.

- Le Gruyère d’Alpage AOC

- Made by hand in alpine huts, this is the most traditional and complex version of the region’s prized cheese.

- Meringues

- Lozenge-shaped meringues, baked until crisp through but not dry.

- Poire à Botzi AOC

- This small, squat Fribourg variety is the first Swiss fruit to gain AOC status. It is cooked to serve with meat or made into vin cuit.

- Sérac

- Many cheesemakers produce this pale summer cheese with leftover whey.

- Vacherin Fribourgeois AOC

- Softer and creamier than its big brother Gruyére, with intense flavour – Vacherin is of the few cheeses made primarily in the winter.

- Vin cuit

- A dark, spiced syrup made from the long-cooked juice of the Botzi pear. It’s drizzled on meringues with crème double or made into a fragrant tart.

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe