Food and Travel Review

Cypriot mothers tell their children: ‘Beware the chameleon! If it bites you on the nose, it will never let go till you put a white donkey on top of an oven.’ It’s a cautionary tale with a moral. The way to sort out unexpected problems is by looking outside the box. In Cyprus’s case, the sticking point is the Green Line dividing the island. Its creation followed an invasion by Turkey in 1974. Since then the two communities, Greek and Turkish, have lived apart.

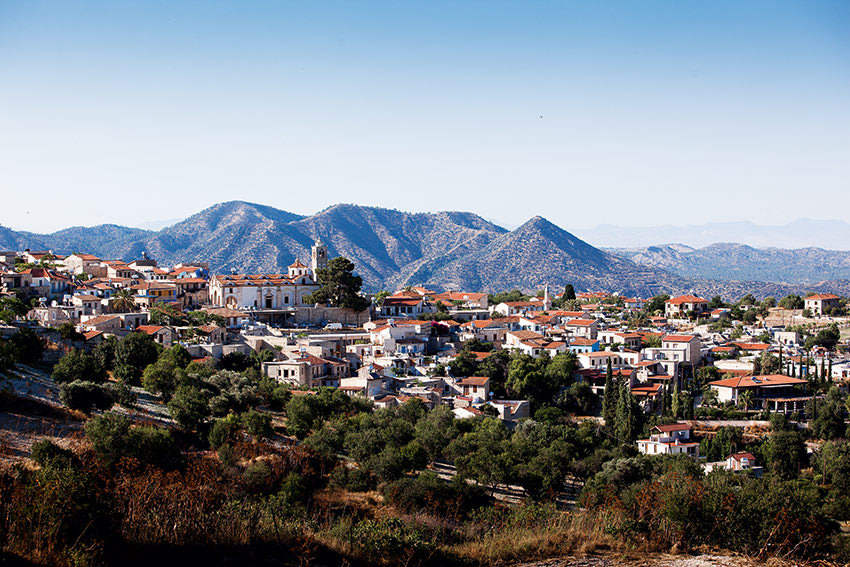

The south – independent, resilient and Greek – is thriving. Resort hotels on the Paphos and Limassol waterfronts jostle for space. Brit expats like to settle here. Ukrainians and Russians buy holiday homes. The richer ones build Orthodox churches. Offshore traders do deals. Farmers hire Vietnamese labour. Even the little old ladies making lace in Pano Lefkara know a trick or two about hard selling.

There’s the occasional grumble among all this good fortune. Offering passers-by cloudy red wine for six euros a bottle outside his house in Omodos, Socrates complains: ‘Perhaps life was better when we were poorer. Back then we’d go to the kafeneion for coffee and we didn’t have to pay for it when we couldn’t afford to.’

His village on the nursery slopes of the Troödos Mountains sits among hump-backed hills of terraced vineyards, peach orchards and olive groves. It prospers on the stream of day-trippers funnelled through its cobbled streets and alleys. At Stou Kir Yianni’s taverna, they graze on meze or sculpted platters of skewered meats. The cooking is good: dolmades rolled neat and thin as cheroots, loukánika (sausages steeped in wine and fried crisp) or afelia (pork simmered with orange peel, cinnamon, cloves and bay leaves).

Letymbou, in the Paphos hinterland, has escaped modernity. An abandoned stone mill stands beside a rusting Land Rover. The church, dedicated to the three-year-old martyr St Kirykos, is locked and Sofia Kyriakou has been up baking bread since 4.30am.

Her whitewashed clay oven, fired with whatever hardwood she can gather with her hands, stands on the terrace outside her house. She says she built her first one when she was 13 to bake pastitsio (a baked pasta dish that closely resembles macaroni). This one will last about nine years before she replaces it. During the week she makes crusty sourdough loaves for her neighbours.

Her party piece is flaouna (a cheese bread) that is still eaten in country villages as a speciality at Easter. It’s a kind of loaf inside a loaf: ‘I dry the cheese for eight days, grate it and mix it with herbs and spices,’ Sofia explains, ‘then I knead it with some eggs, sultanas and bread dough.’ Taking a fistful, she wraps it in a layer of sesamecoated dough, seals it, glazes it and bakes it for half an hour. Dense, chewy, savoury, it’s a rare remnant of feast days past.

For weddings, she prepares another speciality, resi (a cracked wheat risotto) unique to Paphos. It belongs to a culinary repertoire that might vanish in a generation. Some things, like bird-trapping, would be better lost. Poachers, despite the threat of heavy fines, smear twigs with glue to trap small birds such as bee-eaters. They are then roasted and eaten whole. Other traditions still have a future. The man kneeling by the roadside isn’t praying.

He’s picking capers or their stems for pickling. In the hills, wild oregano, thyme, fennel and mint perfume the air. Purple sprays of wild garlic poke through dried grass. Walnut, quince, lemon, loquat and carob trees grow uncared for. It’s a forager’s paradise.

Carob beans dangle from branches in green clusters. When ripe, they turn brown and fall to the ground. They were once Cyprus’s ‘black gold’, its most bankable commodity. The pulp made sweets and pasteli (toffee). Hardened seeds were ground down for thickening gels and celluloid film. Little remains of the industry, barring the Carob Mill restaurant group, a small museum-workshop in Anogyra and two processing plants producing gums, powder and syrup.

Savvas Savva adds a little syrup to the sauce he serves with stuffed chicken breast. He’s head chef at Archontiko Papadopoulou in Kornos. Part museum, part wine cellar, part archive of the island’s gastronomy, part restaurant, it fuses past and present. Its menu flits in almost surrealistic fashion between sea bass swaddled in vine leaves baked on a tile, and cornflour jelly in rosewater cordial topped with candy floss. Snails, stuffed marrows, Easter bread and kataifi (aka shredded wheat) emerge from the kitchens.

For dessert, the kitchen serves filo pastry cups filled with creamy fresh anari (a soft cheese like ricotta that plays yin to halloumi’s yang). They both come from a single batch of goat’s or ewe’s milk. Warmed in a vat with rennet, the milk curdles and breaks into pieces. These are skimmed off and emptied into moulds. Meanwhile the solids left in the whey are heated like ricotta. Strained off the surface, they are ready as soon as they’ve cooled – that’s anari.

Then the other curd blocks go back in the simmering liquid. Cooked till they’re firm, they’re drained, seasoned with mint, folded, and brined – halloumi. Eaten raw with iced watermelon or drizzled with honey it squeaks between the teeth. Dished up as a meze, fried or grilled with oregano or rosemary, it’s crisp and delicious.

The wine cellar at Archontiko Papadopoulou is decorated with massive pitharia (terracotta pots). Elsewhere they lie unwanted in sheds, or upturned and abandoned in undergrowth. Once they contained Commandaria, a sweet wine with a long history. Its name refers to the land owned by the Knights Templars during the Crusades and later by the Knights Hospitaller. It is, though, millennia older. The ancient Greeks called it mana (mother) because they left the lees of old wine in the bottom of the pots before pouring the freshly pressed grape must onto to it.

Ceramic pots have given way to oak barrels, but the wine hasn’t changed since Marc Antony and Cleopatra are believed to have put away a few jars together. Native xynisteri (white) and mavro (red) grapes hang on the vines to ripen. Before pressing, wine-makers sun-dry the fruit to concentrate the sugar. After fermentation, it may be matured for a decade before bottling.

Rich rather than ‘sticky’, it’s neither sherry, nor Madeira, nor tawny port-like. It stands comparison with all three. A generation ago, it was the only distinctive wine on the island. Troödos, its terroir, has started to change, bringing new grape varieties, new methods and new wines. The Vouni Panayia Winery, 1,000 metres above sea level, would not seem out of place on the California Wine Trail. Its white alina (made from xynisteri grapes higher up the mountain) has the freshness of New World sauvignons. Maratheftiko (a native red grape) now competes with syrah, cabernet sauvignon and grenache planted in the region over the past decade.

Lunch on the terrace here reflects the meals owner Andreas Kyriakides’s family eat: a salad of cos, tomato, baby cucumber and feta flavoured with wild herbs; scrambled egg and courgette; a plate of stewed mushrooms; cracked wheat and black-eyed beans; bruschetta with halloumi – and that’s just for starters. Next there are charcoal-grilled spare ribs. For dessert, there’s palouzes (grape juice blancmange sprinkled with nuts).

Slices of soutzouko arrive with coffee. Rubbery like wine gums, their origins trace back to medieval times. Almonds, threaded on cotton, are plunged over and over again in hot, thickened grape sauce and strung up to dry. Seen for the first time, hanging in Limassol’s covered market, they look like beeswax candles.

These same grocery shops sell walnuts, aubergines, carrots and quinces preserved in syrup. The Cypriot addiction to all things sweet is no accident. During the Middle Ages, crops of sugar cane were grown on the island. The Hospitallers owned a sugar mill, still standing next to their castle at Kolossi. So did the Lusignan dynasty that ruled from 1267 to 1489.

The old and the new come together in chef ‘Roddy’ Damalis, christened Herodotus, who was born in South Africa and settled in Limassol 10 years ago. There is no breakage of crockery at his taverna, Piatakia (which translates as ‘little plates’). Instead he covers the walls with them. His menu may owe more than a nod to tradition but he isn’t stifled by it. If the spirit moves him, he’ll stew mushrooms in Commandaria, or bake beetroot in carob syrup. Before he fries halloumi, he infuses rosemary in the butter and squeezes over a little chopped mint and lemon juice.

Cretan dakos (similar to bruschetta) is reinvented in his hands. He soaks dried arkatena (a sourdough and chickpea bread) with water and oil. On top, go air-dried hiromeri (ham cured in red wine from Agros), grated tomato, hard cheese, olives, pickled caper stems and fresh oregano; each ingredient is sourced locally.

He weaves the same magic with kleftiko, the archetypal tourist favourite. ‘It isn’t what my customers expect because they think I’m going to offer them something funky,’ Roddy says. ‘Since I’ve put it on they can’t get enough of it. It’s really surprised me. Locals in the know think you can only make the lamb or goat taste as it should by cooking it in a wood-fired oven. It just isn’t true.’

Roddy is passionate about the island, but he’s not afraid to experiment with its raw materials. ‘I don’t want to see the small cottage industries die,’ he says. Seafood presents him with his biggest challenge. The fish market displays a few red mullet. Prawns may have been flown in from halfway across the world. He grills a mean sea bream on his barbecue – except it’s from the fish farm rather than the open sea. His take on baby octopus, glazed a dark mahogany with cloves and bay leaves, shows what he can do given the chance. As an informed newcomer, Roddy’s views deserve a hearing. He believes Cyprus has a culinary heritage that’s worth fighting for.

It’s 10am in Limassol. A pretty hawker sells pastry turnovers filled with pumpkin and sultanas. Across the street, outside the Fanis kafeneion, a spit turns over a charcoal fire, roasting lamb and chicken. The old men sip their Turkish coffees and watch. Around the corner, they’re digging up the road to pedestrianise the area. On the waterfront, the second largest marina in the Mediterranean is about to open. Making the ancient and modern faces of Cyprus work together will be like… well, putting a white donkey on an oven. Greeks are good at that.

Where to stay

Prices quoted are per night for a double room, unless otherwise stated.

Columbia Beach Resort This resort boasts its own beach. Suites in chalets and on the hillside are cool and well serviced. Rooms from £165. Limassol, 00 357 25 833 000, http://columbia-hotels.com

Grand Resort One of several largish ‘luxury’ hotels on the strip, this one has been newly renovated. It boasts a large well-being centre, and service is friendly and competent. Rooms from £140. Amathus area, Limassol, 00 357 25 634 333, http://grandresort.com.cy

Londa Hotel Chic boutique hotel popular with business and local glitterati. Rooms from £100. Limassol, 00 357 25 865 555, http://londahotel.com

Almyra One of the hippest places to stay on the island, this hotel attracts a young, mostly British, crowd, many with children. Rooms from £172. 12 Poseidonos Avenue, Paphos, 00 357 26 888 700, http://almyra.com

Thalassa Boutique Hotel & Spa This is a great place to unwind. A personal butler is included in the price of the room. Make sure you check out the Psari Seafood Grill, which offers freshly cooked produce and stunning coastal views. Rooms from £165. Coral Bay, Paphos, 00 357 26 881 500, http://thalassa.com.cy

The Elysium You’ll find plenty of restaurants and an excellent spa at this hotel, located in the north of Paphos. Rooms from £157. Queen Verenikis Street, Paphos, 00 357 26 844 444, http://elysium-hotel.com

Travel Information

The currency in the south of Cyprus is the euro (£1=1.2EUR). Cyprus is two hours ahead of GMT. The island has an intense Mediterranean climate with hot summer temperatures from June to September. Rain falls mainly in autumn and winter, other than that, precipitation on the island is rare.

GETTING THERE

Cyprus Airlines (cyprusair.com) flies direct from London Heathrow and Stansted to Larnaca International Airport in the south of Cyprus.

Aegean Airlines (aegeanair.com) flies direct from Heathrow to Larnaca.

RESOURCES

The official site of the Cyprus Tourism Organisation (http://visitcyprus.com) has loads of helpful information for planning your trip. For food-lovers, cyprusgourmet.com offers a useful insider’s guide to what’s going on in the restaurant and wine world.

FURTHER READING

My Little Plates by Roddy Damalis (tapiatakia.com, £30) shows the Limassol celebrity chef doing his thing in the kitchen. This is a good-looking and easy-to-follow book.

Where to eat

Prices are per person for three courses with wine, unless otherwise stated.

Archontiko Papadopoulou Head chef Savvas Savva was World Junior Chef of the Year in 2011. The restaurant is elegant and hospitable and the menu has one or two memorable dishes. From £30. 67 Archbishop Makarios III Avenue, Kornos, 00 357 22 531 000, http://archontikopapadopoulou....

Carob Mill Restaurants A row of four linked restaurants opposite the castle offering very popular al fresco dining; there’s no need to book. From £15. Vasilissis Street, Lemesos, 00 357 25 820 466/464/465/470, http://carobmill-restaurants.c...

Stou Kir Yianni Guest house and taverna in the centre of a picturepostcard village. The food is fresh and very good, especially the afelia and dolmades. From £20. 15 Linou, Omodos, 00 357 25 422 100, http://omodosvillagecottage.co...

Ta Piatakia Fashionable taverna serving modern Cypriot food (owner Roddy Damalis runs innovative cookery courses from the adjoining workshop). From £25. 7 Nikodimou Mylona Street, Limassol, 00 357 25 582 515, http://tapiatakia.com

Vouni Panayia Winery Terraced dining, by appointment only, on a mountainside. Expect a warm welcome and beautiful fresh ingredients. From £20. Panayia, Paphos, 00 357 26 722 770, http://vounipanayiawinery.com

Food Glossary

- Afelia

- Pork braised with herbs and spices.

- Anari

- A fresh goat’s or ewe’s milk cheese, sometimes soft, sometimes lightly pressed.

- Arkatena

- Wholemeal sourdough bread often made with chickpea yeast.

- Barbouni

- Red mullet.

- Choriatiko

- ‘Rustic’ style; a term used to describe mixed salads.

- Fava

- A split pea purée.

- Flaouna

- A spiced cheese bread.

- Glyko

- Generically it means ‘sweet’ but usually refers to fruit (and veg) preserved in a syrup.

- Halloumi

- Semi-hard goat’s or ewe’s milk cheese, often cooked.

- Hiromeri

- Smoked ham that has been marinated in red wine.

- Kleftiko

- Seasoned lamb or goat wrapped in greaseproof paper and oven baked.

- Loukániko

- Smoked pork sausage.

- Lountza

- Loin of pork cured and smoked like hiromeri.

- Palouzes

- A grape jelly-cum-blancmange.

- Pastitsio

- Greek take on macaroni.

- Sheftalia

- A kind of minced meat sausage.

- Soutzouko

- Sweetmeat made with grape juice and nuts.

- Souvlakia

- Skewered barbecued meats.

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe