Tropical Wonders

From the ancient temples of South and Central America to African hot springs and the Chocolate Hills of the Philippines, Jo Davey takes a look at unmissable geological, cultural and natural phenomena

From the ancient temples of South and Central America to African hot springs and the Chocolate Hills of the Philippines, Jo Davey takes a look at unmissable geological, cultural and natural phenomena

The little island of Praslin peeks its bottle-green head out of the great Indian Ocean some 37km from the Seychelles’ main Mahé island. Its white sand shores, daubed with reefs and boutique resorts, are an excellent reason to visit this tropical outpost, but Praslin’s real treasure is at its heart: the island is home to one of the best-preserved primitive palm forests on earth, the Vallée de Mai. Praslin is remarkable geologically and biologically – for starters, it’s a granitic island, a rock rarely found in the midst of an ocean. The forest itself is an ancient leftover from the Gondwana supercontinent and it has remained almost untouched since then. The result is a complex, pristine, prehistoric ecosystem of endemic species: an Eden emerging from indigo waves. Vallée de Mai’s 19.5 hectares are famed for coco de mer, a huge palm with the largest seeds in the world. Each individual nut can reach over 25kg in weight, making them an astonishing (and occasionally dangerous) feature of the forest. Praslin’s sun-stippled landscape contains six colourful palm species, home to endemic animals like the understated black parrot, scarlet-faced blue pigeon and the adorably chubby giant bronze gecko. Exploring its palm trails and waterfalls, look out for tiger chameleon, tree frog, the sickle-beaked Seychelles sunbird and the butter-coloured trumpets of the beautiful vanilla orchid.

After flying into Praslin, walk the Vallée independently or with a local guide – try La Source De Seychelles. Stay at the chic Constance Lemuria or delightful Côté Mer Villa.

lasourcedesseychelles.com constancehotels.com cotemervilla.com

The world’s largest tropical wetland area bleeds from the west of Brazil into Bolivia and Paraguay. The immense Pantanal is often eclipsed by the Amazon’s dark beguiling heart but these glittering wetlands actually hold South America’s highest concentration of wildlife. Better yet, the fauna isn’t fettered by boundless jungle, but patrols out in the open across some 150,000sq km of lowland plains. Only six per cent of the planet is given over to wetlands, which are a vital ecosystem for humans, animals and plants. Even then, that number is half what it once was, making the Pantanal a precious tropical site. As the wet season rolls in, 1,200 rivers burst and flood the region with a mosaic of lakes and marshlands that reflect the cloud-sprinkled skies. Individual mountains abruptly break up these lowlands, the lush peaks seemingly pulled from the pools. As the heat of summer arrives, a wealth of animals fight for their place at these dwindling water holes. This includes the world’s highest concentration of caiman and one of the densest populations of the elusive, beloved jaguar. There’s also the capybara, hyacinth macaw, giant anteater, howler monkey, green anaconda: an unbeatable number of protected species that each play a part in the Pantanal’s complex, connected ecosystem.

Access the park from north or south, flying into Cuiabá or Corumbá. Take a package holiday with Rainbow Tours or

make use of a local guide through accommodation such as

Araras Eco Lodge. Elsewhere, working ranch Caiman Ecological Refuge has gourmet dining and a jaguar habituation project.

Access the park from north or south, flying into Cuiabá or Corumbá. Take a package holiday with Rainbow Tours or make use of a local guide through accommodation such as

Araras Eco Lodge. Elsewhere, working ranch Caiman Ecological Refuge has gourmet dining and a jaguar habituation project.

rainbowtours.co.uk araraslodge.com.br

As the most renowned icon of the Incan empire and one of the biggest tourist draws in South America, the 15th-century citadel of Machu Picchu in Peru’s south needs no introduction. Before 2020, the trail and ruins had reached unsustainable levels of visitors, but the travel hiatus during the pandemic took an unbelievable bite out of Machu Picchu’s mass tourism – much to the citadel’s benefit and Unesco’s relief, it must be said.Numbers still haven’t returned to those pre-covid highs, but they’re climbing, so now could be a good time to visit the bucket- list city. Nestled 2,430m up on a mountain ridge in the Andes’ Cordillera de Vilcabamba, Machu Picchu (meaning ‘old peak’) is an astonishing architectural feat. Its 200-plus structures were built without mortar, their white granite cut to fit perfectly together. Today, its terraces and temples have become an integral part of this theatrical panorama, where the Urubamba river carves through the precipitous, cloud-forested Andes. No matter how many photos you’ve seen, finally laying eyes on the Lost City in person is an unimaginable moment: staring out over it towards the familiar spike of Huayna Picchu peak is like meeting an old friend. Those not wanting to join the growing crowds can instead make for the smaller and much less visited Incan citadel Choquequirao nearby

Take a 3.5-hour train journey from Poroy station near Cusco to Machu Picchu station, or book well in advance for the 4-day guided hike along the Inca Trail. Stay at the stunning Monasterio Belmond in Cusco or luxury Sol y Luna in Urubamba.

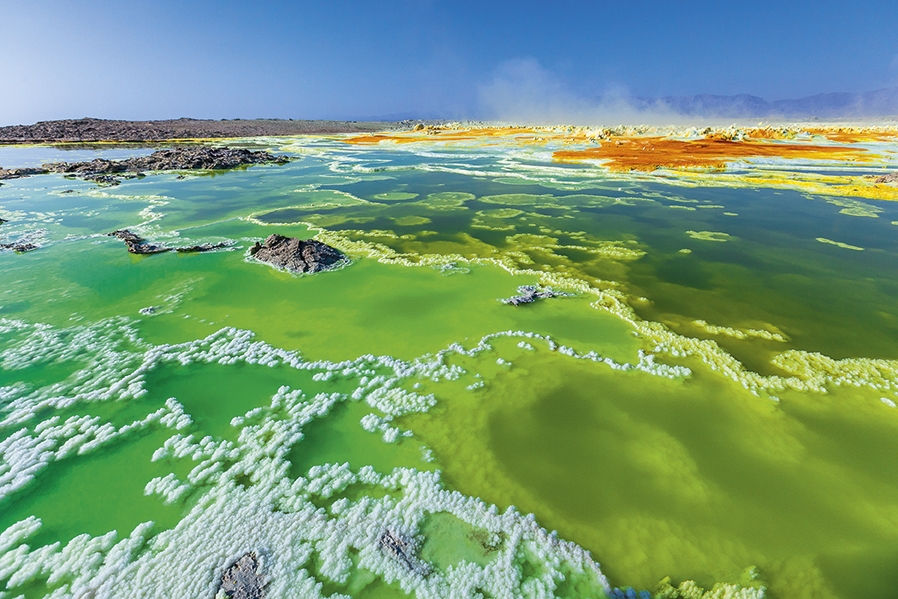

The hottest place on earth happens to be one of its driest and most colourful too. Ethiopia’s Danakil Depression is a bubbling rainbow of crusted snow-white salt terraces, luminous yellow sulphur and iron deposits in shades of lime, teal and terracotta. Mixed by hot springs, this mineral palette paints a sweltering spectrum across an astonishing, alien landscape on the country’s northern border. One source of Danakil’s heat is Dallol Volcano, which lends its name to the area’s hot springs. You’d be forgiven for thinking their simmering shimmer is down to water, but these small craters are actually filled with a highly acidic brine. Danakil’s gaseous geysers help it reach an average daily temperature of 41C – the highest average of an inhabited place – but bracing yourself against the ungodly heat is worth it to see this tropical phenomenon of salt geysers, barren lava fields, hydrothermal chimneys and Gordian salt pillars. Remarkably, the sun-scorched salt plains never stop changing. Danakil is dynamic, the landscape and colours altering within mere days as springs pop up and others peter out. Adding to its Venusian landscape is the enduring smell of sulphur plus the threat of something, somewhere below, exploding upwards. Despite all this, the otherworldly area has been mined for centuries for its salt, contributing to Ethiopia’s ancient salt trade.

Due to its salt value, the area’s seen its fair share of conflict, which makes organised tours a must. Use Wild Frontiers, who visit Danakil as part of a larger tour, with accommodations that could be hotels like Mekele city’s Planet Hotel or desert campsites.

Just north of Bangkok’s tinsel and traffic is the historic city of Ayutthaya. Here, a cavalcade of intricate carvings, vivid murals and elaborate architecture overlooks the natural moat formed

by three winding rivers: the Muang, Pasak and Chao Phraya. Founded around 1350, Ayutthaya became Siam’s second capital, for centuries a centre of international commerce and culture. Burnt to the ground by the Burmese in the 1767, today it’s a vast archaeological park of temples, palaces and monasteries. Its former life as a massive cosmopolitan hub is built into its temples (known as wat), which have elements of Japanese, Chinese, Persian and European techniques and designs.

Among the World Heritage site’s 289 hectares are the Khmer- style Wat Phra Mahathat, a royal terracotta temple and one of Ayutthaya’s oldest. Today it’s best known for its Buddha head, likely toppled off a statue and left to the embrace of a banyan tree’s roots. The resolute face peers out of the grey trunk, eerie and awesome. Arguably the most beautiful is Chaiwatthanaram royal monastery. A broad, ornate central prang tower surrounded by eight sharp chapels, Chaiwatthanaram is an ancient work of art best caught in the late afternoon sun. And the sites keep coming: the needle-like spires of Wat Phra Si Sanphet, one of Thailand’s holiest temples; Wat Lokayasutharam, Yai Chai Mongkhon’s 37m-long white Buddha swathed in saffron-gold silk; and the extraordinary brickwork of Wat Ratchaburana.

An easy day trip from Bangkok – 2 hours by train from Hua Lamphong Station. Or stay overnight at Luang Chumni Village or Baan Thai House to explore further and take in nearby night markets too.

uangchumnivillage.com baanthaihouse.com

While many head to Mexico to explore Mayan culture, north-east Guatemala quietly holds some of the ancient civilisation’s most incredible temples. Erupting from the thick tropical jungle of the Reserva de Biosfera Maya, Tikal National Park’s pyramids are among the largest pre-Columbian temples in Central America. Previously known as Yax Mutal, Tikal was once a booming, 130sq km city that dominated Mayan politics and the economy before being conquered. What remains of Tikal today are powerful stepped structures, their beige and sand-coloured limestone stark against the thick emerald of the ever-chattering jungle. Tikal centres on the Grand Plaza, the former main square flanked by twin Temples I and II, and the North and Central Acropolises. Better known as the Temple of the Great Jaguar, Temple I is the tomb of a victorious king, Jasaw Chan K’awiil I. Standing 47m high, its steep greying steps soar past the tree line and break into boundless sky. The best views of it are gained from climbing its partner across the plaza, the shorter Temple II or Temple of the Masks, built for K’awiil’s wife. Temples and trails surge through Tikal’s wilderness, which echoes with the hoarse whoops of howler monkeys and the bright flash of toucan beaks. The sweat-inducing Temple IV– the tallest remaining pre-Columbian structure, at 65m – is best climbed at sunrise. Turning from its great steps, a golden panorama of Tikal’s entire site unfolds at your feet.

Tikal is reached via the pretty town of Flores,

from where you can book guided tours or join tour-operated shuttles. A good option is a guided day tour with Hotel Casona de la Isla.

On its journey south, the north-east edge of Yogyakarta district takes a sudden sharp turn, skirts around a square block in its way, then carries on as if nothing ever happened. This border is rightly making way for the magnificent temple compound of Prambanan: hundreds of taupe stone temples dedicated to not one but two religions. Built in the 8th century, Sewu was Indonesia’s largest Buddhist temple complex before Borobudur took the crown. When a Javanese king established the Prambanan Hindu temple – Indonesia’s largest – 70 years later, he placed it beside Sewu. He had married a Buddhist princess and together the two temples became a symbol of religious unity and cohabitation in his equatorial kingdom. Successive rulers expanded Prambanan’s gorgeously detailed stonework until the complex was abandoned and left to ruin in the 10th century. For the past century, however, it has been undergoing restoration, its puzzle being painstakingly put back together using original stonework, which visitors can still see carefully piled about the place. And Prambanan’s myriad buildings are jaw-droppingly detailed: in particular, the central compound’s 16 ornate temples. The grandest of these is magnetic Candi Shiva Mahadeva, a 47m-high central tower dedicated to Shiva and carved with lions, kalpaturu trees and mythological kinnara creatures. Standing before it, the platformed temple takes over the horizon, its immense dark towers outlined against the bright Indonesian sky.

Take a day trip to Prambanan from Yogyakarta by taxi or hire car. Stay in Yogyakarta at traditional Rumah Mertua Heritage or eco-conscious Greenhost Hotel.

Somewhere between the Filipino islands of Cebu and Mindanao, two giants began to fight. Days were spent throwing boulders and dirt at each other, exhausting them to the point of surrender and leaving in their wake a legendary landscape. This, at least, is the supposed origin of Bohol island’s Chocolate Hills and one of the more savoury legends passed down about these odd formations. Gazing out over the cones, it’s easy to see why locals looked to mythology to explain them: for over 50sq km, some 1,776 perfectly formed hills erupt across the horizon with a symmetry and uniformity that seems unreal. In the tropical rainy season, the grass-carpeted domes blend into the verdant forest whence they emerge. Come November-May, the grass crisps and discolours, painting the hills the colour of milk chocolate. Giants aside, the hills’ origins are hazy: geologists generally believe they’re the result of erosion and weathering on limestone but nothing has ever been confirmed. As well as putting Bohol on the tourist map, their mystery has earned them a place on

the Philippines’ PHP200 banknote. They’re best seen from the Chocolate Hills Complex in the nearest town, Carmen, or from the lower Sagbayan Peak mountain resort. An alternative is to book a sunrise hot air balloon and look down on the chocolate-drop expanse from above.

Carmen is an hour’s drive from Bohol-Panglao Airport. From Bohol capital Tagbilaran, you can take a private transfer or bus, or join a wider tour with Experience Bohol. Accommodations in Carmen are local B&Bs – try Villa

del Carmen Haven or Matilde B&B – available through booking sites.

SOCOTRA, YEMEN

One of the few areas of Yemen still open to travellers, the entirely unspoilt island of Socotra sits serenely in the middle

of the Arabian Sea. It’s known for its wonderfully diverse landscapes of towering sand dunes, plunging canyons and

the last forest of dragon’s blood trees.

KELIMUTU NATIONAL PARK, INDONESIA

On Flores, or East Nusa Tenggara, there are three mysterious volcanic lakes. These waters on the summit of Kelimutu shine like jewels at sunrise, changing colours with volcanic action. Morphing between electric blue, deep teal and brick red, locals believe the lakes hold the souls of the dead.

KALANDULA FALLS, ANGOLA

Located on Angola’s River Lucala, the Kalandula are Africa’s second-largest waterfalls: at 105m high, 400m across, their rainy season spread is a thunderous marvel. Far less visited by tourists than Zimbabwe’s Victoria Falls, the Kalandula are Angola’s biggest attraction. Whether viewed from above or toured from below, the force of the falls is extraordinary.

GREAT TSINGY DE BEMARAHA, MADAGASCAR

Often called the stone forest, thousands of towering stone shards spike into the sky in this bizarre karst landscape. Featuring chasms that descend 80-120m into the stone, some just 1m wide, Tsingy is also home to multiple endemic species.

BWINDI IMPENETRABLE FOREST, UGANDA

The name of Uganda’s mountainous jungle says it all, although there are still ways in. A vast 32,000 hectares of tangled trees and dark tracts forms Bwindi’s Unesco site and national park, known for its valuable flora, fauna and, of course, mountain gorillas. Only 1,000 of the creatures are left, making a visit here a remarkable, moving experience.

KOMODO NATIONAL PARK, INDONESIA

Extraordinary mountain ridges that plunge down to white sands, turquoise seas with rich coral reefs, abundant mangroves and sun-baked soils: this is the home of the deadly komodo dragon, a see-it-to-believe-it giant lizard. The park is also home to creatures such as the macaque, flying fox, civet, sea turtle and dolphin.

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe