Onions

Michael Raffael peels back the layers to discover the secrets of this pungent, versatile bulb with recipes by Linda Tubby

Knowing your onions’ has meant different things to different generations. According to Nicholas Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (1653) ‘roasted under the embers and eaten with sugar or honey’ they cured coughs. In Acetaria, A Discourse of Sallets, his contemporary John Evelyn claimed they ‘raise Appetite, corroborate the Stomach, cut Phlegm, and profit the asthmatical’. Then, the medicinal and culinary uses of the onion overlapped. Follow the trail into antiquity: Greeks considered them an aphrodisiac; Egyptians treated them as a symbol of eternity; Romans put them in fish sauces.

In the modern kitchen, peeling away the skin of ‘which-onion-for-what’ is tricky enough. Sizes, shapes and varieties come into play. What’s so special about Spanish onions? How many cooks can tell a Welsh onion from a chive? Are silverskins pickling onions? Unless you’ve been to Calabria (or signed up with Slow Food) cipolle di Tropea will mean very little. How did the oignon de Roscoff earn its AO C rating? This, at least, has an answer. It boasts a 300-year-old track record. The name derived from the Breton port. No ship put to sea without taking a large stock on board. Sailors knew it protected against scurvy. In the 20th century, French men wearing berets, dressed as matelots and riding bicycles crossed the Channel. Arriving from Leon in Brittany these ‘Johnnies’ hawked strings of onions door to door. Large, pinkish, not bitter, they lasted all winter. They cost more than the corner-shop greengrocer charged, but were worth it.

Philip Britten came across them when he was chef at London’s Capital Hotel. Now he runs Solstice, a fruit and vegetable wholesale business supplying Mark Hix and Gordon Ramsay. His success depends on sourcing ingredients to keep the stars happy. He’s convinced that newseason onions taste sweeter: ‘I ate this Cevennes onion roasted in its skin in Nice. It was the size of a tennis ball and it was sensational. The flesh was creamy, yellow and you could almost eat it with a spoon.’

Red Tropea cipolle and the small fresh cipolotti are other darlings of fashionable chefs. Francesco Mazzei at L’Anima serves them as a simple salad with tomatoes. They take their name from a seaside town on the bootlace of Italy. Even fully mature, they are gentle on the palate when eaten raw. Tonino, a gelateria near the harbour, serves an onion ice cream as its speciality. They are the best of all red onions.

Britten argues that better-tasting varieties grow near the sea, where they thrive on sandy soil. He compares them with garlic, where freshness also matters. This conflicts with popular demand; the public wants onions all year round, so growers develop varieties that will store for months. ‘I asked a Lincolnshire farmer once,’ he says, ‘and he told me growing onions wasn’t worth his while. English ones are too small and don’t taste as good.’

Other farmers might challenge this. It does have a kernel of truth. The famous organic horticulturalist Lawrence Hills wrote that the onions British sailors took to sea were ‘strong enough to send a pirate’s parrot squawking into the rigging’. Traditionally, the working classes ate them raw. They preferred them more potent to balance out salty meat or cheese. Although taste has shifted – we prefer ours much milder – our standard home-produced crops are thick-skinned and relatively sharp.

Spanish sofrito is better with new season onions, cooked long and slow to extract their sweetness before adding the tomatoes. A confit d’oignon is stickier, even syrupy, prepared in summer. They’re the basis of the Provençal tart, pissaladière. Even piccalilli gains from working with the earliest pickling onions.

There’s a trick to peeling these. Nip off the root end leaving it attached to the skin, then peel them off together. The rest comes away easily, more so if the onion is chilled to start with.

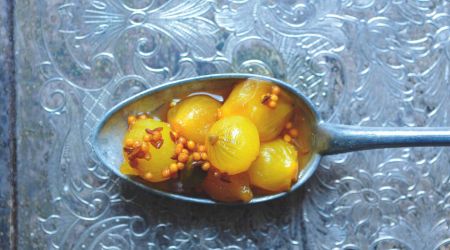

It’s a method that works with silverskins too. Their name is a give-away as to their appearance. The tiny ones are pickled for Martinis, but those a little smaller than ping-pong balls are ideal for glazing (to accompany a coq au vin) or cipollini in agrodolce (sweet and sour).

Chefs haven’t yet latched on to potato onions, but gardeners have. They grow in clusters like shallots, except they’re larger. Once popular, especially in Somerset, eaten with Cheddar and cider, they nearly became extinct. Hills thought they were the mildest native variety. He described them as a variety ‘without tears’.

Scallions aren’t the only wispy-leaved onions. Go to any oriental food store and you’ll find Welsh onions. The name is a misnomer because the plant has nothing to do with Wales. Hollowstemmed, almost bulbless, they could pass themselves off as oversized chives. Neglected here, they are common in south-east Asian cooking (and Jamaican, where they’re called escallions). Welsh onions are also the greenery floating in a bowl of Japanese miso.

At the end of summer, some onions bolt, flower and run to seed before they can be harvested. If they do bloom, cooks can still use the flower-heads. Purple chive flowers are even prettier. Broken up and sprinkled on salads they bring flavour as well as colour – they’re pretty enough to garnish one of Mr Evelyn’s Sallets.

Recipes

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe