Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe

Home to over 500 grape varieties, Georgia boasts a proud culinary heritage influences by both east and west- one expertly championed in London by the executive chef of Kinally in Fitzrovia .

Words by Alex Mead

This article was taken from the April 2025 issue of Food and Travel. To subscribe today, click here.

Despite its Black Sea coastline to the west and a land mass overlooked by four different countries – Russia to the north, Turkey and Armenia to the south and Azerbaijan to the south-east – Georgia is far too often ignored. To many in the west, it’s primarily famed for two things: wine and rugby. And, while he doesn’t proclaim to be an expert in the latter, David Chelidze, the executive chef of London’s Georgian- inspired Kinkally restaurant, knows exactly why the grapes of his homeland are revered.

‘Kakheti [in the east of the country] is a world-famous wine region with around 600 grape varieties and they create so many different styles,’ he says. ‘If you enjoy wine, this place will feel like paradise. But it’s also known for meat dishes like mtsvadi (barbecue) and chakapuli (a meat stew, made with unripe tomatoes). And then there’s Kakhetian oil, whose nutty flavour is perfect as a salad dressing or with canoe-shaped shoti bread.’

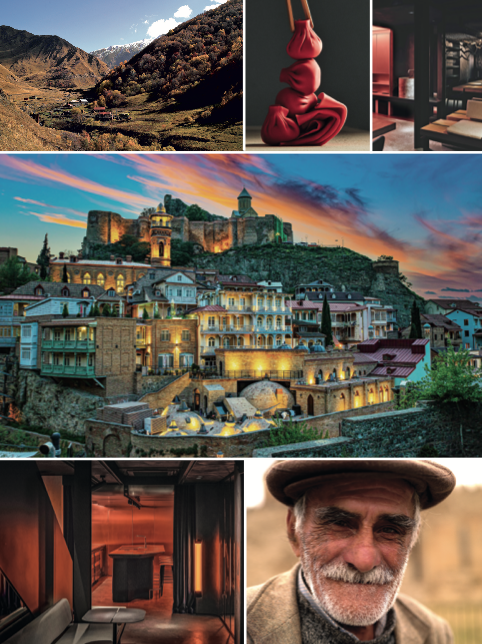

Georgia has been fought over by assorted empires for centuries, bringing a mix of influences and a perfect blend of gothic cityscapes combined with a rich rural landscape and the highest mountain range in Europe. On the border with Russia, with which it has a chequered history – parts of the north are still under Russian control – the Caucasus Mountains make for an almighty backdrop. Home to 5,194m Shkhara on the Georgian side, which tops Mont Blanc by 385m, the Russian side boasts Mount Elbrus which, at 5,642m, is Europe’s highest peak.

The gateway for many is Tbilisi. ‘Like many cities it has an Old Town and a New Town,’ says David. ‘Visitors love the Old Town for its narrow streets, beautiful buildings and traditional Georgian restaurants and bars. But the other side of the city has all the parks, museums, shopping centres and high-rise buildings you expect in a modern city.‘Svaneti has stunning landscapes,’ he continues, taking us to the north-western corner of Georgia. ‘They’ve got the famous Svan salt and, while getting there can be tough, the journey is worth it. You’ll see majestic mountains, including Ushba [also part of the Caucasus Mountains], which many climbers dream of tackling. But it’s worth going there to hike through forests, following lakes and rivers.’

David’s favourite place is, of course, his home city of Batumi in Adjara, south-west Georgia. ‘I love the place,’ he says. ‘It’s unique, with its own special vibe. It’s on the Black Sea, surrounded by mountains, so every sunset looks like a masterpiece. Its architecture is different from elsewhere, it has a different [warmer] climate and Adjarian cuisine. More importantly, in my opinion, it has the tastiest khachapuri [cheese bread, a Georgian staple]. Adjara’s cuisine, especially khachapuri filled with cheese and egg, is more than just food – it’s an art form. ‘I take great pride in being from Batumi. I even love it on rainy days, when the sound of raindrops hitting the ground feels like soothing music and the air becomes crystal clear. ’

The nearby village where he grew up is the source of his earliest food memories. ‘I spent my childhood with my grandmother in the village, where we grew our own vegetables, berries and herbs and had chickens and rabbits. My grandmother had a tough childhood. Having grown up in wartime, she was very careful about food and we used everything: vegetables, fruits and even herb stems. In summer, we canned vegetables, made sauces like adjika [a spicy herb sauce] and tomato paste. We sun-dried tomatoes, apples and hot peppers for the winter.

‘Our small family – me, my sister, my mother and my grandmother – baked our own bread in a tone, a traditional oven. Most often, we made corn bread, called mchadi, and my grandmother would add fried onions and greens. I remember going with her to the mill with sleds carrying bags of corn, and on the way back, she’d take me on the sled – I knew all three mills in our village.’

Dishes were always comforting. ‘For lunch, we’d have thick, hearty soup, like green kharcho, made from a leafy cabbage we grew ourselves. For dinner, it would be either fried vegetables or stewed meat in the oven. Sometimes we even had pigeon, because someone in our family bred them. If we had beef, we’d make ojakhuri, a simple dish of beef with potatoes and, if we had lamb, it would be shila plavi, like a Georgian-style pilaf. ‘The fish dish I loved was fried, breaded hamsi, a Black Sea fish similar to anchovies, though their season is short – from December to February.’ While his grandmother taught him the basics, it was another family member who turned it into a celebration. ‘My Aunt Mary cooked delicious classic Georgian food,’ he continues. ‘She made her own cheeses and churchkhela [candle-shaped sweets made from nuts and fruit], and there was always a variety of dishes. Every time I visited, it felt like a celebration. When I became a chef, she shared her recipes with me, and I still use her tkemali sauce recipe [made with plums]. Thanks to her, I developed a true love for Georgian food and it remains my number one.’

‘During Soviet times, Georgian recipes were adjusted for mass production; modern chefs are changing things back’

David took his first steps to becoming a chef in Moscow. ‘As a young migrant with no specific goals, I took any job,’ he explains. ‘One winter night, while working on a construction site, a friend suggested I look for a job in a restaurant because it was warmer and the food was better.’ After finding work in a Japanese restaurant, he was inspired to study restaurant business and then began a career in hospitality, taking in Turkey, Spain, France and Russia again. Then, in 2023, he came to London for the opening of Kinkally, a restaurant that put the fare of his country firmly to the fore. Co-founder Diana Militski – who had visited Georgia many times – encouraged David to use Georgia as his muse, deciding it was time more people knew about it. And his country inspires everything at Kinkally, from excellent wine and cocktails to dumplings; the restaurant name comes from khinkali, the twisted, meat-filled dumplings that are, effectively, the national dish.

On the changing menu, you’ll also find the likes of cheese-filled megruli khachapuri with autumn truffles, and khinkali packed with wagyu, peppercorn plum sauce and Svan salt. ‘During Soviet times, Georgian recipes were adjusted for mass production and dishes became less diverse,’ explains David. ‘It was all replaced with a recipe book that included around 30 dishes of Georgian cuisine, and restaurants had to cook from it.’ Since independence in the early 1990s, Georgian cuisine, with its use of spices and heat, has re-emerged and now modern chefs are instrumental in changing things back. ‘I read a recipe book about traditional dishes and, if you look at any modern Georgian recipes, they’re almost the same as before,’ he says.

In short, Georgian cuisine is something none of us should be missing out on, preferably alongside fine wines. ‘Proper Georgian food has always been good,’ he concludes. ‘We’ve always known that in Georgia, and now the rest of the world is beginning to find out too.’

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe