Food and Travel Review

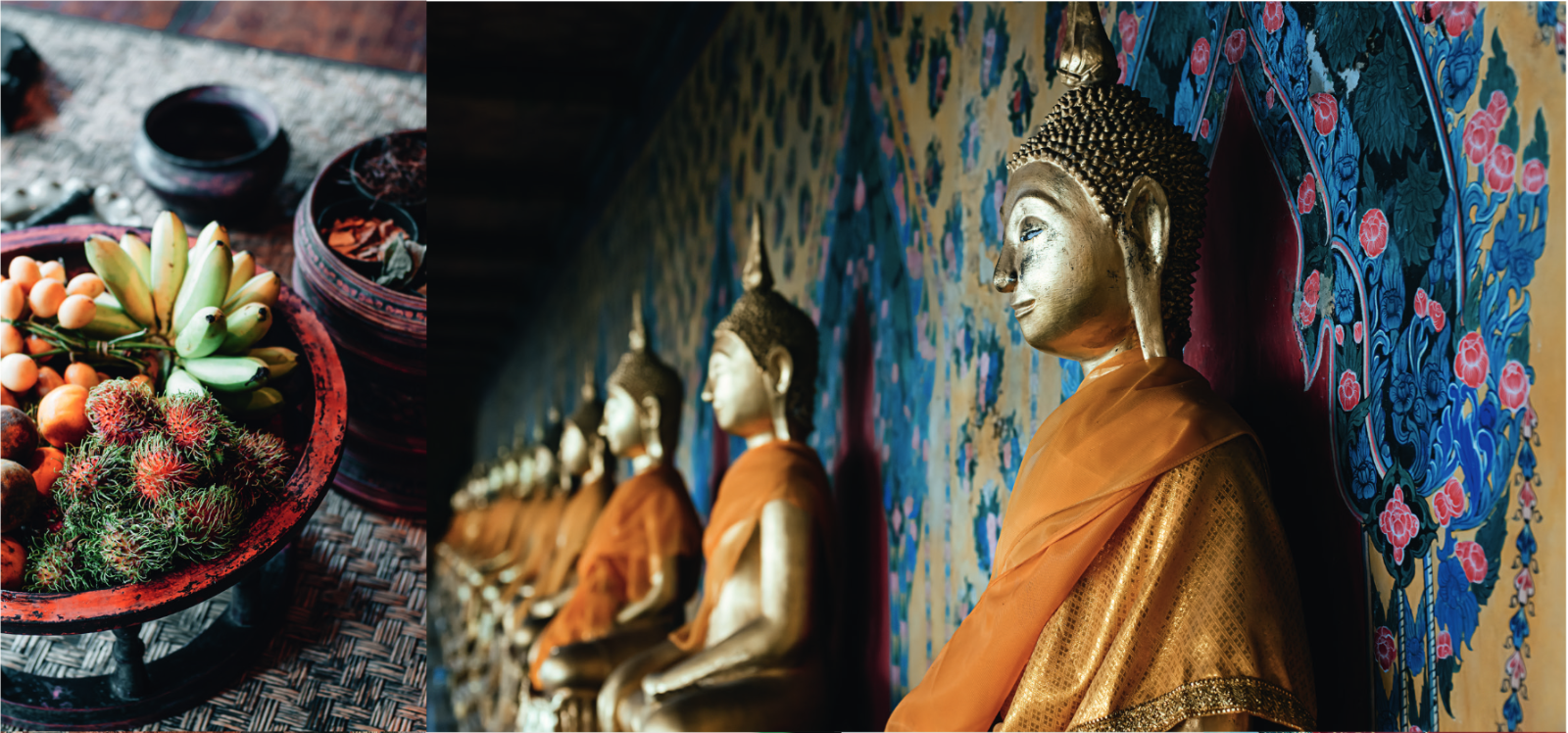

A silky night-time sky slips away as the rising sun kisses the city awake. The Chao Phraya river is dark and slow-moving at this hour, but the imposing temple across from Bangkok's Tha Tien Pier is washed by the morning light. Ten jetties downstream, the first river bus of the day has set out. Until it arrives at the pier, time is measured by the tick-tock of the cross-river ferry that is carrying monks over to Wat Arun, the Temple of Dawn.

It was on this big curve of the river that Bangkok saw its own dawn as capital after Ayutthaya, the former holder of the title, around 80km upstream, fell to warring Burmese in 1767. King and state retreated to a garrison on this site and set about recreating the splendour of the toppled city in the temples and palaces that are seen all around.

In an alley adjacent to one of these treasures, Wat Pho, Temple of the Reclining Buddha, hawkers pour velvety Thai-style coffee through socks or make phad kaphrao moo, a fry-up of minced pork, punchy chilli and a fistful of holy basil, topped with an egg fried so fast that the yolk oozes, but the white has bubbled to a crisp.

Monks hugging alms bowls (bat) head towards the ferry. They walk through mists of tantalising aromas, but breakfast at a food stall is not an option for them, as they eat only what they’re given by devotees. That amounts to one meal to be consumed before noon.

Their belly-sized bowls, just over 20cm wide, hold their day’s rations. After contributions from a dozen or more worshippers, this becomes a salmagundi of sweet and savoury, wet and dry, homemade and off the shelf. Rice, certainly, then a collection of blanched veg, dried fish, fruit, sticky desserts, a spoonful of nam prik kapi, flavour-packed fermented shrimp, pea, aubergine and chilli paste.

Some may be holding a bat that’s worth quite a few baht, having been handmade by the country’s last remaining artisanal metal smiths. Their enclave, Ban Bat, known as Monk’s Bowl Village, was settled in the 1780s by those who escaped when Ayutthaya was razed. Fewer than ten of the original families continue to make bowls using traditional methods.

Ban Bat is on the eastern edge of Rattanakosin, the district that sweeps around the Grand Palace, Wat Pho and Tha Tien, and embraces a hotchpotch of communities: Buddha statue dealers; law students; Chinese dumpling makers in Little India; civil servants; silver merchants; and, of course, the backpackers packed into Khaosan Road’s bars and cafés.

The mighty mural at Wat Trithosathep by artist Chakrabhand Posayakrit holds up a mirror to this mixed crowd. After almost two decades of painstaking work, it depicts stories of heaven and hell, wars and weddings. It’s an affecting piece of art, for in the faces of its many characters, Thai and non-Thai alike, we are all able to see ourselves somewhere.

Temple-goers of 200 years ago must have felt the same when they set eyes on the murals at Wat Suthat, a 20-minute walk south, and close to the centre of the district. Buddhist art enthusiast Aun Apirak says Rattanakosin may have lost some of its significance but the mural is still a draw. ‘They call it the Old Town nowadays, but this temple, its walls, stand the test of time,’ he says. ‘The mural in the ordination hall is considered to be the peak of perfection.’

The hunt for perfection – and food for an empty stomach – was what got MR Thanadsri Svastri up every morning. Thailand’s answer to Egon Ronay, he established the Shell Chuan Chim (‘Shell asks you to taste’) awards in 1962; today, the awards are overseen by his son following a half-billion baht investment by the oil company. MR is similar to ‘Most Honourable’ but despite his high society status, Thanadsri judged food using decidedly low-tech criteria: is it yummy? Is there skill and quality? Would I make a special journey?’

At her food stall in Chinatown, Je Pui has an official Shell Chuan Chim approval sign, symbolised by a lettuce-patterned bowl logo. She also has a framed photograph of herself with Thanadsri and his handwritten verdict of her food that simply says: ‘Absolutely delicious.’ They’re more credible than other awards, Aun explains as he bites into one of her al dente fish balls. ‘But, unlike Je Pui, many winners can’t maintain the quality. The younger generation pay more attention to social media.’ Normally these fish balls are made from one variety of fish, but Je uses mackerel, saury and amberjack, an example of the attention of detail she pays to the taste and texture of this seemingly modest dish. It’s undeniable that a bowl of her noodles is an effortless meeting of textures and technique: slippery wontons and nuggets of minced pork served in a beautifully made bone stock with perfectly cooked noodles.

Methavalai Sorndaeng restaurant isn’t one to pander to millennials, Gen Z or Instagrammers, but then after 62 years of reliably smart cooking it doesn’t need to. Service remains old- fashioned and comforting, with waiters scurrying around in pristine uniforms, and some courses are served on doilies. This stalwart got renewed attention when it received a Michelin star in 2019.

Many of the restaurant’s dishes are ‘royal-style’, which means flavours that are harmonised and neither too spicy or syrupy. ‘Food should come with standard flavour,’ explains Jikki Khunaruang, a local customer of some 30 years’ standing. ‘It’s up to me to make it my own.’ Something she doesn’t need to worry about with her spicy pomelo salad, yam som-o: it’s the perfect balance of sour and savoury, with plump prawns and crunchy dried shrimp.

From humble hawker stalls to swanky restaurants, diners ritually reach for the condiment caddy. This typically consists of fish sauce, sugar, red pepper powder and mild-chilli-flecked vinegar, nam som prik. Sprinklings are added to taste. ‘There are careful balances of salty-sweet-hot-sour,’ Jikki says. ‘And we can tell whether someone understands “Thai taste” by when and how they add these toppings.’

Something that makes adding flavour easier is a tailor-made dressing or chim. One go-to is nam pla prik, a spiky mix of fish sauce, minced garlic and chilli, sugar and lime. At Saw Nawang restaurant, just a five-minute walk from Methavalai Sorndaeng, they add sliced shallot for a mild pungency that emphasises the tenderness of their phad mee krachet dish, a flash-fried tangle of squid legs, vermicelli noodles and water mimosa stalks. Plus, there’s one other essential ingredient that’s tricky to quantify, known as the ‘breath of the wok’. David Thompson, the Australian chef behind London’s influential Thai restaurant Nahm, describes it as a ‘metallic tang’, that scorch to the flavours, smoky and sharp-edged.

A few doors along, at Mit Ko Yuan, the original menu still hangs on the wall as a reminder that little has changed since it opened in 1966. Its Thai-style dishes, notably stir-fried chayote leaves, tom yum goong, exemplify spot-on ‘standard flavour’ cooking. Other items, such as the lip-smacking cow-tongue stew and three-flavoured noodles, nod to the family’s Hainanese roots.

Restaurants can build a reputation from a single ingredient that’s preparation-heavy, such as water mimosa. At Nattaphon, not far from the Grand Palace, their traditional coconut ice cream is the draw, especially the mango flavour, and the mahachanok variety specifically. The sorbet-like young coconut ice is not to be missed either. Owner Rungroj Suwan has refined her three-generations- old recipe, so she no longer has to set her alarm for 3am daily, but she does still insist on using coconuts from Thap Sakae, three hours south of Bangkok on the Gulf of Thailand because, she explains, they’re ‘sweeter and more fragrant’.

To have the pick of the best produce at one of the city’s liveliest markets, Saphan Khao, Jikki hops on her moped at 2am so she arrives when farmers are offloading yesterday’s crops but before hawkers have thought about turning them into tomorrow’s street food. It’s a similar tale at Pak Khlong Market, south of Tha Tien Pier: in the early hours, oily trucks trundle up, tipping out mountains of soapy-fresh jasmine flowers.

It’s adjacent to Pahurat or ‘Little India’, but the aromas that fill the century-old cloth market, wrapped around a knot of alleys and lanes, come from the roti shops and Punjabi confectioners that rub shoulders with its silk and sari sellers. The Pahurat district was home to 19th-century Vietnamese before the South Asians arrived, and then Chinatown spilled over in the mid-20th century. Step into Ji Jong Wa and you’ll be transported back to the Sixties. Its owner hasn’t souped up the interior, but all the effort goes into the signature duck broth, made Cantonese-style, tinged with cinnamon and ladled over yellow noodles and dumplings.

You will find Cantonese and a dozen or more Chinese ethnicities in this part of Bangkok, but Teochew people make up half of the diaspora population. Some put this down to Taksin, the king who spearheaded the move from fallen Ayutthaya, having a Teochew (or Chaoshan in today’s China) father.

‘We are Chaoshan originally,’ Prapon Thayanukul says as he stirs a hot Thai tea at the café counter. He nods to his mother, Kanchana, who was born at about the time her father-in-law started this business in 1933. It’s called On Luk Yun (‘Happy Garden’) and opens at 6am for east-west breakfasts. Think scrambled egg with cocktail franks and fried Chinese sausage.

Like canned milk tempering local tea, Chinese cookery has had an emulsifying effect in kitchens through Thailand and down the Malay Peninsula. Singaporean visitors, for instance, lap up dishes with similarities to their cuisine. This includes sangkhaya, a coconut curd made daily in the café by simmering egg yolks, coconut milk, sugar and pandan (the regional ‘vanilla’). The recipe was introduced by Japanese-Bengali-Portuguese chef Maria Guyomar de Pinha to royal kitchens in 17th-century Ayutthaya.

On Luk Yun opens on to Charoen Krung Road, one of two arteries that run through neighbouring Chinatown. During the day, the commercial heartbeat of the district is in its store-lined back streets and epic bazaar, Sampeng Lane. But at nightfall, when it feels like the oven door has been shut on Bangkok, the focus is on Yaowarat Road. Here, restaurants turn inside-out and hawker stalls create a log jam on pavements as the neon lights shine.

Yaowarat is turned into a food warrior assault course. Hungry contenders must table-hop from shop to stall. Get ready to encounter challenges: chicken feet; pig brain; shark fin. Saunter through the fumes of chilli and hot herbs, musky durian fruit, grilling fish... Suddenly, there’s the flash of a cleaver, lobster claws clatter in a wok and someone’s goose is cooked.

And then it’s time to slow down at Chujit’s stall with a bowl of silken tofu in a ginger firewater. A sweet way to end the evening, watching the city drive by. Like the Chao Phraya river, Yaowarat’s traffic flows inexorably, carrying with it Bangkok’s todays and yesterdays into tomorrow, when a new dawn will break.

Where to stay

Baan Noppawong A charming boutique in a traditional teak-built house,

conveniently situated between Khaosan and Dinso Roads on a quiet lane.

Doubles from £60. 114 Soi Damnoen Klang Tai, 00 66 2 224 1047

Grand China Hotel With recently refreshed rooms, this hotel scores highly for its location on Yaowarat Road. With all that food on the doorstep its restaurants may be (unfairly) overlooked, but the 24th-floor bar is handy for a nightcap with a panorama. Doubles from £58. 215 Yaowarat Road, 00 66 2 224 9977, grandchina.com

Sala Rattanakosin Stylish accommodation, with several rooms overlooking the river, and a rooftop restaurant and bar for sunset views of Wat Arun. Doubles from £124. 39 Maharat Road, 00 66 2 622 1388, salahospitality.com/rattanakosin

Travel Information

Bangkok is located in the south of Thailand. The city sits on the Chao Ph

raya river, approximately 40km from the Gulf of Thailand. Thai is

the official language, though English is widely spoken. Currency is the

Thai Baht (THB), and time is seven hours ahead of GMT. Direct flights

from the UK to Suvarnabhumi International or Don Mueang International

Airports take around 11 hours 30 minutes.

GETTING THERE

Thai Airways fly direct from London Heathrow to Suvarnabhumi

International. thaiairways.com

British Airways offer daily direct flights from London Gatwick to

Suvarnabhumi. britishairways.com

RESOURCES

Tourism Thailand is the official tourist board. Their website is full of

helpful information to help you plan your trip. tourismthailand.org

Where to eat

Prices are for a meal for two, excluding drinks, unless otherwise stated

Chikatcha This 80-year-old corner coffee shop, now cheerfully

run by third-generation owners, is handy for a hot or iced beverage

and snack. Find it at the entrance to Phraeng Phuton Road on

which Nattaphon (see right) is located. Hot drinks from £2.

550 Tanao Road, 00 66 81 559 9608

Chua Kit Huat A Teochew (Chaoshan) restaurant in the ‘Chinatown

extension’ on the west side of the river – don’t miss the superb goose

simmered in a deep gravy, which has a base that’s 80 years old.

From £17. 330 Din Daeng Road, Thonburi, 00 66 2 437 2427

Chujit A dessert street stall specialising in bua loy, black sesame-stuffed

glutinous-rice dumplings in ginger broth. Desserts from £1. Open

from 5pm. At junction of Yaowarat and Mangkhon Roads

Je Pui Noodles Fish balls par excellence, best in soup with noodles,

wontons and ‘long fish’. From £5. 5 Maitrichit Road (opposite the

entrance to Wat Phlap Phla Chai), 00 66 2 224 4351

Ji Jong Wa Old-school Cantonese eatery, where the duck broth

is smoky and sweet and the noodles and wontons are made in house

every morning. From £6. 868 Phiraphong Alley, 00 66 2 222 5973

Kan Kee Nam Tao Thong Herbal tea emporium making a sweet tea (supposed to stimulate appetite and banish mouth ulcers) and a bitter option (cooling). Tea from 70p. 670 Charoen Krung Road, 00 66 2 623 0718

Methavalai Sorndaeng Vintage chic, but nonetheless faultless cooking, with occasional live music and waiters who dress like the ship’s purser. From £25. 78/2 Ratchadamnoen Klang Road (opposite Democracy Monument), 00 66 2 224 3088

Mit Ko Yuan Most eateries on Dinso Road are worth exploring, and this may be a good starting point: many approve of its zesty tom yum goong, but other classic central Thai dishes like the phad kaphrao are exemplary. From £7.186 Dinso Road, 00 66 92 434 9996

Nattaphon Ice Cream Homemade traditional dairy-free coconut

ice cream (flavours include Thai tea, chocolate, matcha and durian

in season) plus toppings (eg peanut, corn kernel, lotus seed). Ice cream

from £2. 94 Phraeng Phuton Road, 00 66 89 826 5752

Old Siam Plaza This ‘Little India’ shopping mall is handy on two counts:

the refreshing aircon, and the ground-floor snack market that is a

worthwhile source of freshly made sweets and savouries. Snacks from 60p.

On the corner of Triphet and Phahurat Roads, 00 66 2 226 0156

On Luk Yun ‘Thai–American’ all-day breakfasts – the best option is the

steamed white bread with sangkhaya coconut jam. Breakfast from £1.25.

72 Charoen Krung Road, 00 66 85 809 0835

Saw Nawang Anything from the wok here is delicious: the phad mee krachet is renowned, while the suki haeng (dry-fried glass noodles) is unusual but equally tasty. From £7. 156/2 Dinso Road, 00 66 2 224 2588

Food Glossary

- Cha yen/ron; gafae yen/ron

- Iced/hot Thai tea; iced/hot Thai coffee — with condensed milk and sugar

- Foi thong

- ‘Gold threads’, sugary egg yolk strands, from a Portuguese recipe introduced to 17th-century Ayutthaya palace kitchens

- Hwan, priao, phed, khem, khom

- Sweet, sour, spicy, salty, bitter

- Khai dao

- Fast-fried egg (add mai suk to specify runny yolk or suk mai if you prefer a hard yolk)

- Khanom kudi chin

- ‘Chinese church cake’, a sponge cake traditionally made in the one-time Portuguese enclave of Kudi Chin on the Thonburi side (west bank of the river)

- Kreung gaeng/nam prik gaeng

- Paste using fresh/dried chilli, shrimp paste, shallot, garlic, lemongrass; the building-block of many dishes and available to buy ready-made at markets

- Nam chim

- Pouring sauces usually based on fish sauce or vinegar, including nam pla prik (the most basic version of fish sauce with fresh chilli), nam chim kai (sweet chilli sauce sometimes with chopped garlic) and nam chim chaeo (with toasted sticky rice, popular with grilled pork or chicken)

- Phad kaphrao moo

- Fried holy basil, chilli and garlic with pork (or moo sap, with minced pork; kai, with chicken; or neua, with beef)

- Sen mee

- Vermicelli rice noodles, in dishes such as phad mee krachet

- Sen ya

- Broad flat rice noodles, in dishes such as pad see ew

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe