Food and Travel Review

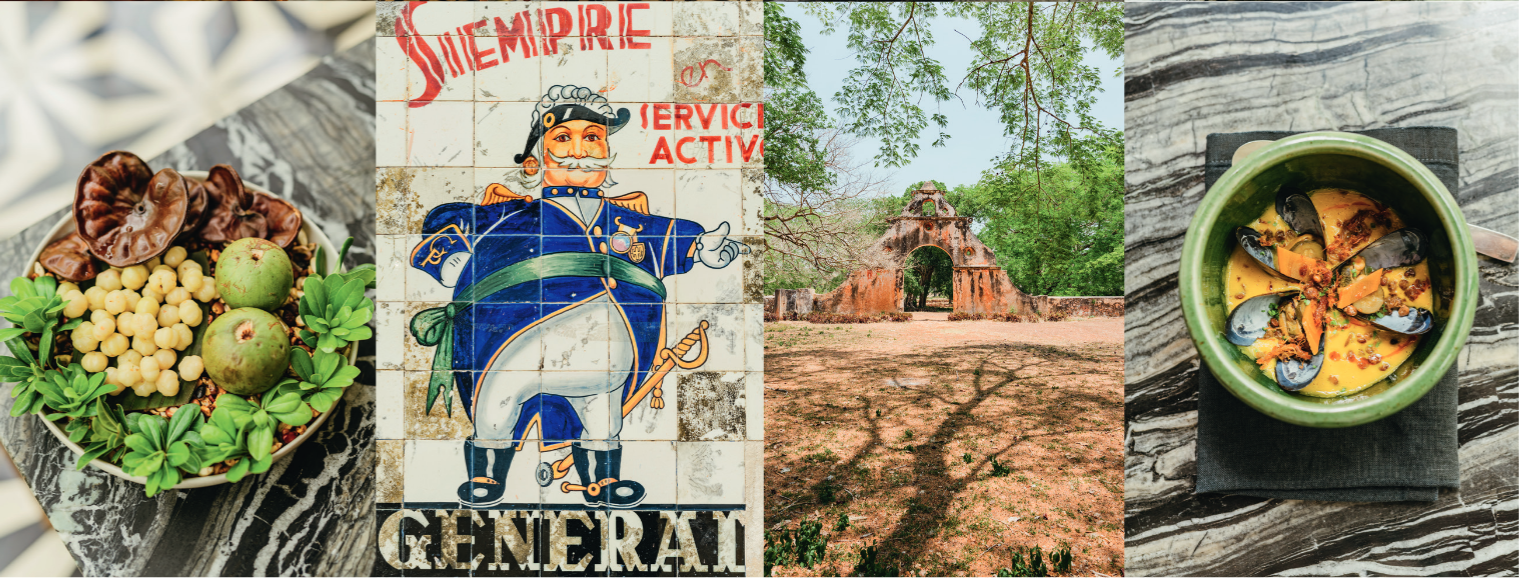

Yucatán life blooms from great tracts of monotone. The north coast of Mexico's south-eastern state seems desaturated: a landscape of flat scrubland and sharp agarve regularly scorched by a dogged sun. But from out of this brush

erupts an irregular Mayan world — stepped limestone temples,

orchards of bitter oranges, cities coloured like summer bouquets.

The Maya are often consigned to templed antiquity, but still make up around 60 per cent of Yucatán state’s demographic and their traditions thrive. At Pablo Evelia Burgos Suarez’s farm in Yáaxhom — a citrus-centred community with some of Yucatán’s most fertile soil — Mayan techniques are used to tend diverse crops. He plants chillies as insect barriers, leaves surplus produce around cocoa fields to encourage pollinators, harvests in the full moon when fruits are plumpest, and leaves weeds to help keep the earth cool.

There’s only so much ancient techniques can do against

modern heat, though. Passing tilled fields of parched maize and

new papaya, the ground crunches underfoot like kataifi. Pablo

points out the scorched leaves on the baby trees: ‘That’s one of

the problems of the sun: it burns,’ he says. As climate change

introduces more extremes, it’s an extra challenge for Yucatán’s

farmers. Despite that, the 20ha family farm remains productive

and when avocado, watermelon, calabaza (pumpkin) seasons

come round, they can’t eat or sell them quickly enough. Pablo

supplies local fine-dining hotels like Chablé Yucatán and Arca in

Tulum: one of Latin America’s 50 best restaurants. But even when

business is good, farmers feel the squeeze.

‘The government once shared the cost of water, but now it’s all on the producers. Then there’s the problem of insurance companies,’ he explains, gesturing to a neighbour’s field of heat-ruined tomatoes. ‘They don’t protect fields damaged by the sun.’ So what can his neighbour harvest instead? ‘Resignation,’ he says, with a half-laugh huff.

It’s clear Yáaxhom’s community is close-knit. Pablo wanders into a neighbour’s garden laden with jackfruit, guanábana (soursop) and jocote trees. A so-called Mexican plum, jocote or ciruela are more like a sour little mango, powdery and puckering and vitally refreshing. At a friend’s house, Pablo spots a ripe mango in an enormous tree. With a long hook and much manoeuvring, the fruit is thrashed down to eager hands. It’s piping hot: sun-baked into tender, juicy flesh that dribbles like syrup over chins, fingers, palms. It’s a glorious mouthful of Mayan produce. Pablo hands over armfuls of calabaza, melons and citrus with an invitation to come back for avocado season and the anticipated abundance.

On the outskirts of Valladolid, a small central city with a pastel palette, the Cen Canché family are stoking the heat at their home kitchen, Aldea Xtabún. All hands are on deck as grandfather Juan and uncle Miguel fire up the píib. This is the powerhouse of Mayan cuisine: a hole dug in the earth and fed with wood, into which marinated meat is placed and covered to cook low and slow — traditionally overnight. Today the women of the family, headed up by grandma Irma and aunt Martina, are making kaax píibil. This chicken dish begins with a paste called recado rojo, made using a metate grinding stone. Martina demonstrates the push-pull roll needed to mince alliums, herbs and spices, the result fragrant with warm cinnamon, robust oregano and the tickle of black pepper. Chicken and paste are mixed by hand with soaked achiote — scarlet seeds straight from their tree that dye the knuckles russet. It’s finished with bitter orange, or naranja agria: a much loved Yucatecan ingredient originally introduced by colonial Spanish. It’s all lowered into the glowing píib and covered with corrugated iron and soil, as blackbirds and great-tailed grackles whoop and whistle overhead.

Meanwhile, under fronded shade, Irma shows how to make the bastions of Yucatecan cuisine. Like the majority of the family, she speaks mostly Mayan and her instructions are explained with soft, hot hands. Dressed in a traditional white-and-floral hipil dress, she toasts calabaza seeds on a comal griddle, swirling them with strong fingertips. They’re ground with onion, garlic, salt, chilli and charred tomatoes to create sikil p’ak: a smoky Mayan dip. Next, Irma turns to tortillas, patting masa (corn mash) into quick, thin rounds before they too face the comal. Even for foreigners, the smell of tortillas is strangely nostalgic: a salt-maize waft that permeates kitchens, stalls, petrol stations across Mexico. She makes some into huevos encamisados – the tortilla prised apart, an egg dropped into the envelope and returned to the hotplate.

Tamales, arguably Yucatán’s best export, follow. Today, the steamed dough features chaya: an ancient superfood often likened to spinach. Chaya grows prolifically in Yucatán, sneaking into everything from juices to desserts. Sacred to the Maya, you must ask the plant’s permission before harvesting or find yourself stung by its needle-like hairs.

Dinner begins with the ritual of putting out the píib. The blanketing soil is hosed down, steam billowing out in great, mulch-flavoured plumes. The men then grab spades and scrape down to metal, before hooking out the casserole to serve. It’s a beautifully balanced mouthful of mild citrus, peppery achiote bitterness, spices and herbs with chicken so succulent, so soft, it’s hard to believe it’s actually meat.

For dessert, Martina feeds toasted cinnamon and cocoa beans into a hand grinder. Brown shavings wriggle out from the wheel accompanied by the deep aromas of spice and cacao. The mix is kneaded into rounds with honey from the indigenous, endangered and stingless melipona bee and served with xtabentún — a local liqueur made with fermented honey and anise. Home-cooked píib meals like these are time-consuming, often reserved for celebrations like Hanal Pixan, the Maya’s Day of the Dead.

But kaax píibil is a mere featherweight to Yucatán’s most renowned dish: cochinita (pork) píibil. Santiago Market, in state capital Mérida, is the humble home of the best. Its still air smells like pork lard, tortillas and tang. Old tinselled decorations — the kind of metallic foil reminiscent of Eighties attics — flutter under silent, spinning fans. The market once housed a small taqueria run by Lupita Solis’s parents. She played with Pedro from the stall next door while their families worked. Several years later, playmate became husband and together they took over the taqueria. Today, Taqueria La Lupita’s tables have boldly spread across the floor of Santiago Market, and in the early morning, regulars are already lining up to eat and commune. ‘For us, it’s an important moment of the day,’ explains Lupita, ‘to get together with all the family over food. People think this is just a market, but even when people get married, they come here to celebrate.’

Most start the day with La Lupita’s unbeatable tortas. Not actually cakes, but baguettes, these are an unexpected late addition to the Mayan menu. Some believe they were brought to Mexico by invading French in the 1860s, others from the French- owned Caribbean. Regardless, these sandwiches are now a Yucatecan staple, the bread perfectly suited to soaking up cochinita’s recado rojo sauce.

Haunches of pull-apart pork — another Spanish import — are kept warm beneath a plastic guard, arguably there to keep hungry punters at bay. On one side sits lechón, seasoned and slow-cooked suckling pig, on the other the fabled cochinita píibil. Don Pedro Medina, a neatly-moustachioed man bursting with good nature, offers a torta of each and bowl of sopa de lima broth. All are extraordinary. The soup’s lime cuts through the spheres of fat floating on each sour spoonful, while shredded chicken and tortilla strips provide chew. The lechón’s crunch of heavy-duty crackling is lightened by a chunky salsa full of the region’s famous habaneros. Chillies here produce the kind of burn that makes you confront the mechanics of eating, as lips and gums numbly smoulder for ten minutes after. The cochinita píibil torta, however, is transcendent: the pulled pork so moist it drips, a dribbling bite of smoke, salsa and fire bled into crunchy white bread. It may be the finest mouthful in Mérida, but it comes with an accompanying lethargy that locals call mal de puerco: pork sickness. Still, it lures Lupita and Pedro’s family in every week, a mealtime bonding session strengthened by the family discount.

Markets are at the heart of these classic Mayan meals. Some 40km north-east of Santiago Market sits the town of Motul. This low-lying city is chock-full of churches and local businesses: launderettes, printers, mechanics, an inexplicable number of piñaterias with their doomed, smiling cartoons. There’s a hand- crafted beauty to the place, its raggedy walls painted with pretty, homemade shop signs — even familiar Coca-Cola logos come with pencil marks and brushstrokes.

Motul is known for its eponymous huevos motuleños — a legendary egg dish created by a local chef for visiting diplomats, using what few ingredients he had. For the past 24 years, the city’s Mercado Municipal has been the home of huevos motuleños, thanks to Doña Evelia.

Evelia summons coffees with a smile and a flick of clacketing, gold wrists. She used to be a primary school teacher, and it shows in her kindly command. ‘For me,’ she says, ‘the story of huevos motuleños is part of the story of Yucatán.’ The dish is simple: fried tortillas, black beans and fried eggs topped with a tomato, onion, pea and ham salsa – Evelia has added a regional habanero kick to her tomato sauce. The magic happens in a minuscule kitchen that originally served sandwiches to just four tables. Now it turns out hundreds of plates a day for a sea of tables covering the market’s top floor. The trick to her signature dish: ‘selecting the best- quality ingredients – and having a lot of love’.

Far from the tattered tinsel and plastic cutlery of Yucatán’s

markets is Ixi’im, restaurant of Chablé Yucatán’s grand 1800s

henequen hacienda. Located to Mérida’s southwest, Ixi’im offers

fine dining and one of the largest tequila collections in the world,

but it’s rooted in Mayan traditions. Chef Luis Ronzón and his team

source produce from local providers like Pablo and from Chablé’s

own prolific gardens, where they’ve also dug a píib. They prepare

their blue, red and white corn tortillas using Mayan nixtamalization,

a process where corn is cooked in a 1 per cent limestone solution

to increase nutrition, flavour and reduce mycotoxins.

These colourful tortillas feature on Ixi’im’s extraordinary ten- course tasting menu; an inspired modern take on Mayan cuisine and Yucatecan produce that never falters. Dinner opens with a corn consommé, with seaweed, smoked chilli, coriander and lime. It’s piquant, comforting, extraordinarily smooth — like drinking satin. It’s followed by black aguachile, calabaza píibil, grilled broccoli with peanut mole. There’s cochinita, braised short rib, melon kakigoori (shaved ice) and a magnificent chocolate tamale.

It features venison too: a meat found on ancient Mayan menus. Hunting deer is strictly licensed but they wander Chablé, fated to occasionally appear in píibil venison risotto with pickled radishes, topped with crispy dehydrated oregano leaves from the garden.

Luis prefers not to be too perfectionist in his plating, allowing the dishes to speak of Yucatecan nature. ‘Everything is natural here, we do everything from scratch,’ he states as the tamale oozes liquid chocolate — their own, naturally — and that heady cinnamon. ‘Even at taquerias, nothing is synthesised or processed. That’s just the way the average Mexican eats.’

Despite being stuffed and seared with heritage, the Yucatecan plate is forward-thinking: from Mérida to Valladolid, traditions have been maintained with reason rather than blind devotion. Mayan food, above all, adapts, weathering colonial influences, modern life and the occasional wrath of a vengeful sun.

Where to stay

Chablé Yucatán Colonial hacienda south of Mérida with two restaurants, cenote,

spa, tennis courts and grounds. Out-of-the-way resort luxury at its finest. Doubles

from £535. Tablaje 642, Chocholà, 00 52 55 4161 4262, chablehotels.com

Hotel Mesón del Marqués Courtyard hotel with excellent restaurant and rooftop bar overlooking San Servacio Church. Doubles from £85. Calle 39 No 203, Colonia Centro, Valladolid, 00 52 985 856 3042, mesondelmarques.com

Kahal A traditional Mérida building with 12 king bedrooms, bar, restaurant and

library featuring local art and photography. Doubles from £155. 00 52 999 238

8469, Av Paseo de Montejo 500B, Mérida, kahalhotel.com

Verde Morada Hotel Encuentro 19th-century masonry house with lovely garden and traditional Mayan elements. Doubles from £113. Calle 41A No 209, Colonia Sisal Calzada de los Frailes, Valladolid, 00 52 985 130 0669, verdemorada.mx

Travel Information

Yucatán is a south-eastern state of Mexico, bordering the Gulf of Mexico on the northern part of the Yucatán Peninsula. Its state capital city, Mérida, has twice won American Capital of Culture thanks to its mix of rich Mayan heritage and colonial influences. Although there is an international airport in Mérida, UK flights do not go direct. Instead, 8.5- hour flights run from London Gatwick to Cancún and the 4-hour onward drive to Mérida takes in the cities of Valladolid and Motul. Currency is the Mexican dollar (MXD), although the US Dollar is often accepted, and time is 6 hours behind GMT (but note that Cancún is 5 hours behind GMT).

GETTING THERE

British Airways have daily flights from London Gatwick to Cancún.

britishairways.com

GETTING AROUND

Car hire is the best way to visit Yucatán’s best cities and remoter sights,

such as its Mayan temples and cenotes. Avis and Europcar both have rental

offices at Cancún International airport. avis.co.uk europcar.co.uk

RESOURCES

Yucatán Travel is the official tourism website, full of insights and

information to help you plan your trip. yucatan.travel/en

Where to eat

Prices are per person for three courses with drinks, unless otherwise stated

Almar Marisquería Chef Gustavo González serves exquisitely fresh seafood on

the outskirts of Mérida in a restaurant full of laughter and locals. From £25.

501 Av Maquiladoras, Industrias No Contaminantes, Mérida

Cantinas Local cantinas are a must-visit: tuck into cocktails served with plentiful

botanas at El Gallito and La Negrita. Cocktails with botanas from £2.50. El Gallito:

Calle 45 No 51A, between Calle 62 and 60, Centro, Mérida, 00 52 990 165 0409;

La Negrita: Corner of Calle 62 and 49 No 415, Centro, Mérida, 00 52 999 267 9582

Huniik Chef Roberto Solís’s vast tasting menu is an extraordinary journey through Yucatecan food and Mérida markets. Tasting menus from £93. Calle 60 No 415-B, between Calle 45 and 47, Centro, Mérida, 00 52 999 912 6244, huniik.com

Ix Cat Ik Rustic Mayan kitchen with a pretty garden that serves traditional family

recipes. Try chaya soups, longaniza sausage and shrimp with recado negro sauce.

From £40. Calle 39 No 158, Militar, Valladolid, 00 52 985 104 1605, ixcatik.mx

Micaela Mar & Leña Wood-fired kitchen and oyster bar serving a broad menu. Popular, lively and with an excellent cocktail bar. From £37. Calle 47 No.458, Centro, Mérida, 00 52 999 518 1702

Nol Award-winning chef Erick Bautista Chacón combines Oaxacan and Yucatecan

flavours in a contemporary menu: try the grasshopper-dusted xilotes and crudo

de pescado. From £40. Calle 60 No 473, between Calle 55 and 53, Santa Lucia

Park, Downtown, Mérida, 00 52 999 175 8624, nolrestaurante.com

Food Glossary

- Achiote

- Also known as annatto, these nutty, sweet and peppery red tree seeds are key to recado rojo spice paste (see below)

- Aguachile

- Spicy Mexican dish of raw shrimp or fish, likened to ceviche

- Botanas

- Regional snacks served alongside drinks in traditional cantinas, usually free with your drink. Each cantina has its own variations

- Chaya

- Yucatecan shrub whose leaves are used in daily drinks and dishes – its leaves are poisonous if uncooked and its sap is caustic

- Cochinita píibil

- Pork marinated in recado rojo (see below) and cooked in a píib oven dug into the ground

- Guanábana

- An avocado-sized green fruit, also known as soursop, with complex flavours ranging from creamy to sweet and sour

- Henequen

- An agave farmed in Yucatán for its sisal-like fibre

- Huevos encamisados

- Eggs cooked inside a tortilla

- Huevos motuleños

- Egg dish from Motul, made with ham, peas, fried tortillas, black beans, tomatoes and onions

- Jocote

- Small, tart, plum-like fruit, also known as ciruela

- Kaax píibil

- Marinated chicken cooked in a píib

- Lechón

- Slow-cooked suckling pig

- Masa

- Mash made of corn and water that makes the base of tortillas

- Naranja agria

- Bitter or sour orange, key to many dishes

- Recado rojo

- The most common spice paste of Mayan cuisine, made using achiote, which give it the red colour, and naranja agria (see above)

- Sikil p’ak

- Dip made with toasted, blended calabaza (winter squash) seeds

- Sopa de lima

- Soup made with tortilla strips, shredded chicken and lime, popular for breakfast

- Tamale

- Masa dough steamed in corn husks or banana leaves

- Torta

- Sandwich made using a baguette, commonly stuffed with lechón or cochinita píibil (see above)

- Xtabentún

- Liqueur made with anise seeds, fermented honey and rum, usually served straight or added to coffee

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe