Desert dreams

Arid, isolated and sparsely populated, the world’s deserts are the last great bastions of pastoral life. As Imogen Lepere discovers, they make a fine base for adventure

Arid, isolated and sparsely populated, the world’s deserts are the last great bastions of pastoral life. As Imogen Lepere discovers, they make a fine base for adventure

The monsoon whips through Rajasthan from July through to September, but the Thar is so remote the plains and mountains which surround it syphon off the moisture long before it reaches the desert. All that is left are hot, strong winds which keep the sand dunes in a state of perpetual motion. To outsiders, it’s a formidable place to venture because the topography can be unrecognisable within the space of a few hours; each shift is a photo opportunity. Only four-wheel drives with GPS and native Marwari horses, which have been bred here since the 12th century, can find their way reliably. Hire them with Mandawa Safaris and hack through the dazzling scenery to Pushkar, which hosts one of the biggest camel fairs in the world every autumn. The Silk Road once ran through the centre of the desert and you can retrace it on camel back, following in the footsteps of spice traders and silver merchants. The area around Jaisalmer is particularly rich with memories, including the deserted town of Kuldhara and several romantic forts. Jaisalmer itself is an amber dream of a city, dominated by a medieval citadel that looks like a giant sandcastle from the outside, and is a warren of streets swaddled by tapestries and perfumed by wafts of incense within.

TOP TOUR

Far and Ride combines riding safaris in the bed of

the Luni river with visits to local villages and desert camping.

The trip culminates with three days at the Balotra horse fair,

which sees 7,000 steeds and their owners gather in south-west

Rajasthan. From £3,484pp including seven nights’ full-board

accommodation, horse hire and a guide. farandride.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

Sujan The Serai is set on an 40-hectare

estate ensuring a sense of utter seclusion. The 21 tented suites

are the last word in desert luxury, while activities include

everything from jeep safaris to campfire performances by

Manganiar folk singers. Doubles from £494. sujanluxury.com

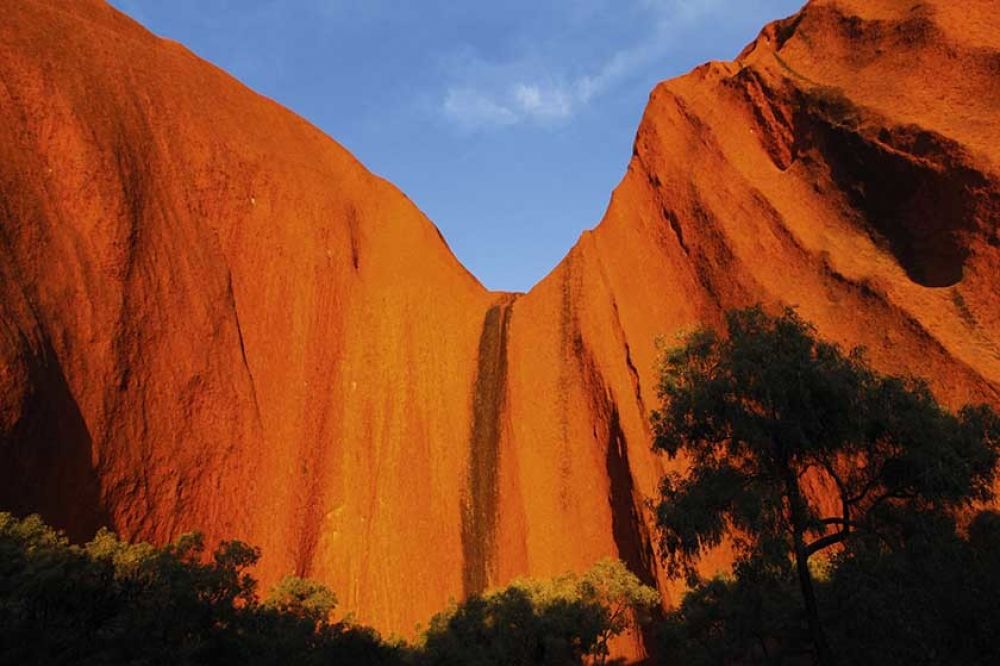

It’s here that you’ll find Australia’s Red Centre, an intoxicatingly alien landscape of dirt the colour and texture of burnt biscuits, bare sandstone and gorges such as Redbank, where you can float in an outback water hole while being serenaded by a didgeridoo. The second largest desert in the country, the Great Sandy swarms across 284,993 square kilometres of the far north west of Australia. Its most famous draw is Uluru (formerly Ayers Rock), the sole survivor of an ancient mountain range which once divided the Great Sandy Desert in two. The fissures and caves around its base are home to several unique species of plants, as well as sacred Aboriginal sites which date back to the period known as the Dreamtime. Learn how to interpret these mysterious markings as well as how to survive in the outback from an indigenous guide, an experience that can be arranged at the Uluru- Kata Tjuta Aboriginal Cultural Centre. The area looks equally impressive from a hot-air balloon or on a scenic flight in a helicopter, which can easily be booked through local hotels. The Karlamilyi National Park is home to the desert’s only river, the Rudall. The paperbarks and cork trees on its banks are rich in bird life such as fairy-wrens and majestic falcons.

TOP TOUR

Trailfinders offers a fantastic Top End and Outback tour.

Drink up views of the desert sunrise from the famous railway The

Ghan, explore Alice Springs, the outback’s most cosmopolitan city

and watch the sun set over Uluru. From £1,547pp for eight nights’

accommodation, transport and meals. trailfinders.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

Longitude 131 is a collection of 16 permanent

tents kitted out with custom-made wooden furniture and king-sized

beds draped in luxe fabrics. Each offers unparalleled views of Uluru.

The spa uses plants from the outback in massage oils, while the

restaurant’s bush menu includes finger limes and muntrie berries.

Doubles from £1,714. longitude131.com.au

In the Mongol language, Gobi means ‘waterless place’ and it’s true that much of the terrain comprises dusty plains that are as empty as the sky above. However, the landscape is much more varied than that. There’s rippling steppe cropped by tiny cashmere goats, the startling moonscape of the Flaming Cliffs, where Roy Chapman Andrews discovered a clutch of fossilised dinosaur eggs, and the haunting beauty of the Khongoryn Els (singing sands), which stand in peaks like freshly whipped egg whites. Make the gruelling climb up these behemoth dunes at sunset and you’ll feel as if you’re seeing the world at the dawn of time, before humans had expanded into all but its most clandestine corners. A huge draw of any trip to Mongolia is its nomadic culture. Roughly half the population carry on as their ancestors have done for 3,000 years, living in gers (yurt-like tents), raising horses and two-humped Bactrian camels. A visit to a local family can involve anything from sipping airag (fermented mare’s milk) around the fire, shearing a camel or riding horses bareback – be warned, they’re famously skittish. A new international airport due to open late 2018 will make the Land of the Blue Sky more accessible than ever.

TOP TOUR

Mongolia Luxury Travel offers a 4x4 tour of the Gobi Desert’s sights

combined with a visit to the Terelj National Park, where you’ll find an

enormous statue of Genghis Khan. From £1,766pp including six nights’ full

board accommodation in gers, travel and activities. mongolia-tours.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

Three Camel Lodge has 40 opulent gers with en-suite

bathrooms. There’s also a cinema and massage tent. Doubles from £1,657pp for two nights’ accommodation, transfers and meals. threecamellodge.com

On the west coast of Namibia, Atlantic breakers pound an ochre beach which has swallowed more than 81,000 square kilometres of the country. Over the course of 55 million years this great sea of sand has expanded steadily, and now flows across the borders into Angola and South Africa. To the south, in the Sperrgebiet National Park, wind whips through the valleys faster than anywhere else in southern Africa, creating huge rippling dunes. Along the coast, sea mists nourish a surprising variety of wildlife. A jeep or walking safari is the best way to engage with it. Look out for the endemic golden mole and the warbling song of the dune larks, while further inland you’ll see herds of Hartmann’s zebra searching for succulents in the foothills of the Naukluft Mountains. Ancient rock paintings at Brandberg and Twyfelfontein tell the story of the thousands of years of man’s struggle against the ferocious weather, making for a fascinating day trip. On the banks of the Kuiseb River, you’ll see the dusty villages of the Topnaar tribe, who still eke out a living by harvesting Nara melons. Sossusvlei is a salt and clay wasteland surrounded by towering 300m terracotta dunes. Explore it on a quad bike hired from your camp for an exhilarating sense of freedom.

TOP TOUR

Tok Tokkie Trails offers walking safaris through the

Namibrand nature reserve. Spot barking geckoes, bat-eared

foxes and dancing spiders, before returning to a luxury camp

for a three-course meal. From £362pp for two nights’ full-

board accommodation, guide and transfers. toktokkietrails.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

Sossusvlei Desert Lodge has 10 ultra-luxe

suites carved from glass and stone, each with their own

fireplace and 180-degree views. The hotel can arrange

everything from quad biking to stargazing excursions on the Skeleton Coast. Suites from £342pp. andbeyond.com

Often overlooked by tourists in favour of religious sites such as Jerusalem, the Negev Desert holds half of Israel in its dusty clutches. Its tawny landscape is scarred by memories of long vanished rivers and occasional geographical marvels such as the Ramon Crater, which is the biggest erosion circle in the world. Despite the fact that temperatures regularly soar to 48C –Nabataean kings used to be deliberately extravagant with water to impress guests during the Hellenic period – the desert has its own wine route. Between the surprisingly sophisticated city of Be’er Sheva and the artistic hill town of Mitzpe Ramon, a smattering of growers such as Boker Valley Vineyards use computer-controlled irrigation systems to produce gutsy pours with a distinctive, slightly mineral taste. Drive along Road 40, stopping off at cellar doors along the way. Although much of the desert is dirt punctuated by jagged rocks, the loose sand of the dunes outside Be’er Sheva is an ideal nursery for fledgling sand boarders and you can rent equipment from any number of providers in the town. Once home to King Herod, the Masada fortress towers 450m above sea level. Climb it at dawn to watch the sun creep over the Moab Mountains before rejuvenating with a restorative a soak in the Dead Sea.

TOP TOUR

Desert Eco Tours offers jeep adventures which

follow the ancient spice route (with its fascinating remains)

through the Ramon Crater to the Dead Sea. From £680pp

for three nights’ accommodation in Bedouin style tents,

transport and two meals a day. desertecotours.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

Beresheet Hotel is perched on a cliff above

the Ramon Crater and has magnificent views from its infinity

pool. Exteriors artfully blend into the rocky landscape, while

contemporary interiors nod to nomadic culture with traditional

rugs. Doubles from £265. isrotelexclusivecollection.com

The largest hot desert in the world,

the constantly shifting sand of the

Sahara burns through ten countries,

taking dramatic mountains, black

sand volcanoes and the River Nile

in its stride. In the current political

climate, the Moroccan section is

the most accessible, yet it manages

to retain its sense of utter isolation.

Toil up one of the Erg Chegaga sand

dunes and you’ll feel as if you’ve

landed on the moon. Given that the

harshness of the Sahara hasn’t

managed to break them over 4,000

years, it isn’t surprising that the

Berbers have successfully resisted

the might of the Roman, Arabic and

French empires, emerging from

each invasion with their culture and traditions intact. Today, their

khaimas (camel skin tents) and

herds of shabby goats and camels

provide meagre sustenance as they

always have done. Most guides have

relationships with local families,

who welcome visitors into their

homes for cups of sweet mint tea in exchange for goods which are

difficult to get hold of, such as

simple clothes. In the foothills of

the Atlas Mountains, the tiny town

of Agdz rises from an oases of

palm trees like a mirage. Ancient

mudbrick buildings guard

honeycomb streets which you can explore on bicycle, stopping

off at the Thursday souk for hand-

woven baskets and pottery.

TOP TOUR

Laila Sell offers yoga retreats in the Sahara. You’ll split your time between practicing, camel trekking and exploring sites like the ancient citadel at Ouled Driss. From £1,175pp for 12 nights, including accommodation, meals and classes. yogalaila.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

Merzouga Luxury

Desert Camp nestles among the

dunes of Erg Chebbi in Morocco.

Expect 15 spacious tents with

comfortable beds and colourful

carpets. A private dinner under the

stars, complete with champagne, is

not to be missed. Doubles from £287.

merzougaluxurydesertcamps.com

High up on a bone-dry plateau just south of the Sahara Mountains, Wadi Rum is a bizarre, primeval mass of soaring red rocks, criss-crossed by a complex artery system of sun-drenched chasms. When TE Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia) visited in 1912 he described it as ‘vast, echoing and God-like’, adjectives which still fit today. Watch the sun set from the slopes of Jebel Qattar with a steaming cup of Bedouin tea (black tea with sage) to truly appreciate the different shades of gold, red and orange which make up this extraordinary Unesco World Heritage site. Rock climbers will find a host of epic massifs to explore. Jebel Rum towers 1,754m above Rum Village and a local guide will be able to lead you to the summit via the steep pathways used by ancient Bedouin hunters. Scramble 80m to the top of Burdah Rock Bridge for magnificent views or set out to hike the sandstone fissures. You’ll see inscriptions in Aramaic (thought to be the language of Christ) of the names of the Thamudic tribesmen who trod the same path more than 2,000 years ago. Although several tribes have links with this wilderness, the Al Zalabieh live exclusively in Wadi Rum’s 720sq km and are its official caretakers. While they mostly work in tourism now, traditional culture is still strong. Zarbs (feasts prepared in buried charcoal ovens) are still common and the plaintive sound of the oud (pear-shaped string instrument) can frequently be heard reverberating through the still desert air.

TOP TOUR

G Adventures offers a multi-sport trip including a visit to the rock city of Petra by candlelight and camping in Wadi Rum. From £1,069pp for seven nights’ full-board accommodation, activities and travel. gadventures.co.uk

HOTTEST HOTEL

Bedouin Nomad Adventures is an intimate camp run by locals. A handful of tents with single beds, share a communal bathroom. They can organise everything from wild camping to jeep tours. Doubles from £26. bedouinnomads.com

This fierce wilderness is smeared mostly across California and parts of Nevada, Utah and Arizona, but nowhere is its savagery defined more clearly than in Death Valley National Park. Rattlesnakes hiss in the foothills, abandoned towns such as Rhyolite hint at the hardships suffered by ore miners, while the salt flats in the Badwater Basin are the lowest point in North America at 86m below sea level. The best way to explore it is by car, as temperatures regularly hit 50C. Further south, where the Mojave melts into the Colorado Desert, Joshua Tree National Park contains the densest forest of these strange looking plants (actually a member of the agave family) in the world. Arboreal coyotes slink between them and more than 240 bird species migrate through it on their way to the Salton Sea, so it’s a hot spot for twitchers. In the golden hills east of Bullhead City, the speed limit is 120km, and there are plenty of dry creek beds and dirt trails, perfect for off-roading.

TOP TOUR

Intrepid Travel offers a Wild Western USA Tour, a road trip which takes in the West Coast’s top sights. You’ll see the Grand Canyon, LA, Yosemite, plus Death Valley and Joshua Tree. From £1,395pp for 10 nights’ accommodation, car hire and entrance fees. intrepidtravel.com

HOTTEST HOTEL

La Quinta Resort is a testament to man’s

determination to assert himself over nature, even in the least

hospitable environments. Since 1926 it has attracted film

stars from nearby LA, lured away by the promise of a luxury

desert experience. Expect a championship golf course and

several pools. Doubles from £291. laquintaresort.com

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe