Raspberries

Tart and sweet, these perfumed fruits pair beautifully with vanilla, almonds, chocolate and even game. If, says Clarissa Hyman, you can resist eating them au naturel.

To give someone a raspberry is a delicate, poetic, Jane Austen-esque gesture: to blow them one, however, is something else altogether. It seems curious that the fruit has attracted such a vulgar double meaning, but it is true the raspberry induces both delight and distress. The latter, in food circles at least, is largely on account of a design fault – its seeds.

To fans such as myself they are barely noticeable and, when so, are part of the berry’s unique charm. Exquisite in shape and colour, the fruits possess a captivating fragility and an intermingling of both tart and sweet juices. The flavour shot is intense. As a wise woman once said, nobody can be insulted by raspberries and cream.

On the other hand, some people simply cannot get over the seeds. They get stuck in their teeth. They are rough and raspy in the mouth. Such fussy types insist on sieving them out when making jam, a wimpish move that, to my mind, strips the fruit of character.

Believed to originate in the east, raspberries have a rich, exotic look and beautiful perfume that stamps the berry, according to writer Waverley Root, as ‘Made in Asia’. The finest raspberries of antiquity were said to have been found on Mount Ida in Turkey, which accounts for the botanical name, rubus idaeus.

Raspberries are said to have been around since prehistoric times but were only widely cultivated in Europe during the 16th century. At this time they were mostly cooked or used as the basis for cordials and drinks, as fresh fruit was commonly regarded as harmful to the digestive system.

The Old English name for raspberry was ‘raspis’, connected possibly to ‘raspise’, a sweet, rose-coloured wine. It was also once called a ‘hindberry’, its leaves loved by female red deer (hinds). Uncultivated fruit has an outstanding flavour, so canes (cuttings with a piece of root) taken from the wild are often planted by horticulturalists and crossed to improve yield and disease resistance. But its natural habitat is damp woods, and it likes a cooler climate. Some of the best commercial raspberries in Britain are grown around Blairgowrie in Perthshire.

The raspberry is a richly coloured, triangular fruit, with velvety, slightly hairy drupelets clustered tightly around a central core. When ripe, the small, cuplike fruit comes away from this solid centre, which remains as a hard, white cone on the stem. It makes the picking easy, and the consumption easier still.

Raspberry cultivation is not especially difficult: it is more about a need for space than constant care. The main thing to consider is that once a cane has fruited, the whole branch dies and should be cut away to allow new canes to rise from the base. Different varieties crop at different times: Glen Ample is the most widely grown, with the extra-large berries appearing throughout July. Glen Moy is also regarded as a connoisseur’s choice: the Royal Horticultural Society has given the fruit its Award of Garden Merit. Heritage Red is a late-fruiting berry with excellent flavour that also makes good jam, as does Tulameen, but the mainstay is Autumn Bliss. As gardener Sarah Raven notes, the good thing about autumn berries is you don’t have to net; at this time of year, birds have plenty of choice of feed.

Red is the usual colour, but there are also white, yellow and golden raspberries. Tart black ones, which are known as Black Caps, are common in the Eastern US and Canada, and are good for cooking, juicing and country wine.

In summer and autumn, look for firm, dry berries with a good colour. They’re best when fully ripened on the cane and are highly perishable, so avoid punnets stained with juice: this is a sign the fruit is past its best. Don’t buy ones that are damaged, shriveled or have brown spots, and try to use them on the day you buy them.

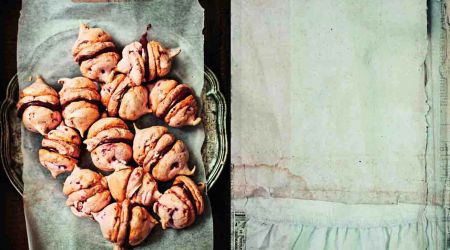

If you can resist eating them ‘au natural’, there are endless ways to prepare them. Paul Hollywood uses the fresh fruit in Danish pastries, Peter Gordon suggests folding them into a mix of cream, yoghurt and honey to make an easy honey fool pudding, while Eric Lanlard adds basil to the berries to boost their flavour in an intriguing baked raspberry and basil tart.

Raspberries are a quintessential fruit of summer, part of seasonal pleasures such as pavlova, peach Melba, raspberry cranachan and summer pudding. Their flavour pairs with almonds, honey, vanilla, cinnamon, chocolate and red wine, but also works with poultry and game. Raspberry vinegar was once a popular remedy for sore throats or as a basis for summer drinks diluted with soda. It came back into vogue with the fashion for nouvelle cuisine in the latter years of the 20th century, and it still has its place in the repertoire of marinades and salad dressings.

And if you’re still worried about those pesky seeds, I can only use the F-word. Floss.

Recipes

Get Premium access to all the latest content online

Subscribe and view full print editions online... Subscribe